Battle of Leipzig (Battle of the Nations)

Date and place

- October 16th to 19th, 1813 near Leipzig, Saxony, Germany.

Involved forces

- French army (190,000 men), under Emperor Napoleon the First.

- Prussian-Austrian-Russian-Swedish coalition (330,000 men), under General Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, Prince Karl Philipp Fürst zu Schwarzenberg and Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, Crown Prince of Sweden.

Casualties and losses

- French army : 38 000 killed or injured and 20 000 prisoners.

- Prussian-Austrian-Russian-Swedish coalition : 54 000 killed or injured.

Aerial Panorama

Apogee of the Saxon Campaign, the Battle of the Nations [Völkerschlacht], also known as the "Battle of Leipzig", was the greatest confrontation of the Napoleonic Wars, and Napoleon I's heaviest defeat. It put an end to French hegemony in Germany.

General military situation

The Battle of Dresden offered Napoleon a triumph without a future. The results of the pursuit proved disappointing. Worse, too fiery or poorly supported by Marshal Laurent de Gouvion-Saint-Cyr, Dominique-Joseph Vandamme was surrounded at Kulm and had to capitulate with 12,000 men. Other defeats of the Emperor's lieutenants, conceded during the same period, finished annihilating the effects of the victory obtained under the walls of the capital of Saxony: Étienne Macdonald was defeated by Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher on the Katzbach, Nicolas Oudinot by Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte at Gross-Beeren.

Napoleon, however, began the campaign by placing himself in a strategic waiting position in Dresden. His intention was to take advantage of this central position to successively defeat his various adversaries. In fact, he mainly had to rescue his marshals, whom the enemy attacked preferentially. This resulted in marches and counter-marches that exhausted the inexperienced soldiers at his disposal. Indeed, the weakness of the French cavalry made it difficult to gather information on the enemy's movements. Conversely, the latter, correctly informed, systematically evaded Napoleon to reserve his blows for the marshals of the Empire. Subjected to this regime, the latter showed signs of demoralization: Michel Ney, faced with Napoleon's reproaches after his defeat at Dennewitz, asked in vain to be removed from this hell

.

Faced with the worsening situation, the Emperor concentrated his forces in Leipzig. The convergence of enemy movements towards this city had not escaped his attention. However, he could only gather, in the best case scenario, 250,000 men there to face the 400,000 allied troops approaching. However, confident in victory, he left 30,000 men in Dresden under the command of Gouvion Saint-Cyr, in order to block the future retreat of the allies. He set up his HQ in Reudnitz on October 14.

Napoleon's objective was to prevent at all costs the three enemy armies - the Bohemian armies commanded by Karl Philipp Fürst zu Schwarzenberg, the Silesian armies led by Bluecher and the Northern armies led by Bernadotte - from coming together and forming an enormous mass to which he was unable to oppose equivalent numbers. However, the nature of the terrain around Leipzig made the joining of the enemy armies problematic anywhere other than in the city itself. By holding the city and its outskirts, the Emperor could therefore attempt to defeat the various Allied contingents separately before they met, however close they might be to each other.

On the coalition side, the movements followed a strategy that consisted above all in cutting off communications between France and the Grande Armée. From this point of view, the defection of Bavaria - which took place on October 8 -, the immediate entry into the campaign of its troops and their march towards the Rhine, is a major success, ignored by Napoleon until October 17.

The terrain

Leipzig lied south-east of the confluence of the Parthe and the Pleisse, itsef a tributary of the White Elster, on a wide plain dotted with woods and hillocks. To the south, hills sloped gently from the Pleisse to the heights north of Wachau. From there, in an easterly direction, two parallel lines of modest hills extended. The southernmost ones stretched from Auenhain to Grosspösna; the northernmost ones – the Galgenberg and then the Kolmberg – dominated the villages of Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz. To the east, between the Kolmberg and the Parthe, the terrain was open. To the north, between the Parthe and the Elster, there was no lack of rolling hills, but none of them was capable of supporting a solid defensive position.

To the west, on the left bank of the Elster, the Lützen road constituted the French line of retreat. The river divided into multiple branches, transforming the area into a marsh. Fords and bridges, however, were numerous. Nevertheless, the presence of woods ultimately made the area unsuitable for significant troop movements. This configuration persisted southward near the Pleisse, whose left bank (west) was difficult to access, and which could therefore only be crossed in a few places. The Connewitz bridge thus gained strategic value.

The city of Leipzig was part of a rectangle of 1000 meters on each side. It was fortified, but its walls with almost filled-in ditches protected it only very imperfectly. Four gates pierced this approximately square-shaped enclosure. Those of Grimma to the east, of Saint-Pierre to the south, of Halle and Ranstadt to the north. The last two gave access to the Lindenau road by the bridge over the Elster. The suburbs themselves were fortified, but the quality of their walls left something to be desired.

Placement of French troops

CONTINUER ICIOn October 15, Napoleon travelled through the region and placed his troops according to the natural obstacles formed by the Elster, the Pleisse and the Parthe between the various enemy armies.

In Leipzig itself, Margaron and Arrighi, the heads of the garrison, remained within the city walls.

In Lindenau, General Pierre Margaron had taken up position with 15,000 men to protect the army's lines of communication.

Facing south-east, where he believed the bulk of the fighting would take place, he deployed the Grande Armée in a semi-circle, from the Pleisse in the south to the Parthe in the east. The main line was around Wachau. The arrangement was as follows:

- Józef Antoni Poniatowski (appointed Marshal of the Empire the day before, VIII Corps), reinforced by Charles Augereau (IX Corps), set up the furthest south, at Markkleeberg. Near them are the cavalry corps of Pierre-Claude Pajol (5th) and François-Etienne Kellermann (4th)

- Going to the left (east), Claude Victor Perrin kown as Victor(II Corps) occupied Wachau, supported by Marie-Victor-Nicolas de Faÿ de La Tour-Maubourg (I Cavalry Corps)

- Jacques Alexandre Law de Lauriston (V Corps) defended Liebertwolkwitz

- Macdonald (XI Corps) and Horace François Bastien Sébastiani (II Cavalry Corps) formed the extremity of the device, towards Kleinpösna

- The Guard and the I (La Tour-Maubourg) and V (Pajol) Cavalry Corps were kept in reserve

- The VI Corps (Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont) was considered a general reserve, at least until Bluecher appeared to the north. In total, Napoleon opposed 96,000 men to the 140,000 of the Bohemian army.

To the north, on the Parthian, where 25,000 French could have to hold off 70,000 Russo-Prussians of Bluecher, Napoleon was content to take defensive positions and to garrison the villages of Gohlis and Pfaffendorf, very close to the city, with troops. Ney had received an expanded command on this front, thanks to which he theoretically had 55,000 fighters at his disposal. His authority extended over:

- Joseph Souham's III Corps

- Henri Gatien Bertrand's IV Corps

- Marmont's VI Corps

- Jan Henryk Dąbrowski's 27th Infantry Division

- General Jean-Thomas Arrighi de Casanova's III Cavalry Corps, formed by the divisions of Jean-Thomas-Guillaume Lorge, Jean-Marie Antoine Defrance and François Louis Fournier-Sarlovèze .

But the bulk of his infantry was still on the way: Souham at Mockau, 15 km to the northeast, Dąbrowski at Ploesen, 5 km behind. The first should arrive on the 16th.

While waiting for them, Marmont watched the road to Halle with 20,000 fighters spread out between Möckern and Eutritzsch. He was tasked with containing Blücher and Bernadotte if they showed up. Ney, positioned north of Parthia, was to quickly come to support him with 35,000 men if the need arose.

- Jean-Louis-Ébénézer Reynier and his VII Corps were still far away, on the road to Eilenburg

In the evening, certain indications suggested that the enemy could appear on the road to Weissenfels, with a view to joining the Army of the Danube by Zwenkau or Pegau. Napoleon instructed Marmont to monitor this movement from Lindenau and Leipzig. Then he devoted himself to dictate his orders for the following day.

The Allied plan

On the Danube Army side, discussions were in full swing. The Russians and Prussians wanted to deploy their offensive on the right bank of the Pleisse and the Elster. The Austrians would prefer to operate towards Dölitz. The final plan would combined the two. A frontal assault, led by Russians and Prussians under the command of Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly (Mikhail Bogdanovich Barclay de Tolly, Михаи́л Богда́нович Баркла́й-де-То́лли), would focus on the axis linking Liebertwolkwitz to Markkleeberg. It would align 70,000 men.

The main attack would be carried out on Dölitz and Connewitz, between the Elster and the Pleisse. Its aim would be to outflank the French right. Maximilian Friedrich von Merveldt would lead it. He would have 40,000 Austrians at his disposal.

In addition, Johann von Klenau would try to bypass the French left while the 25,000 men of Ignáz Gyulay von Máros-Németh und Nádaska (often called Giulay in French texts) would try to cut the Grande Armée's line of retreat at Lindenau and then link up with Blücher.

The latter, about twenty kilometers from Leipzig, was champing at the bit waiting for the signal to attack. However, when it sounded, he hoped to benefit from the support of the Army of the North. Bernadotte, at the head of the latter, finally made progress after some tergiversations which had delayed him, to the great displeasure of the Prussian general-in-chief.

October 16th. Battle of Wachau

The battle began at around 9 a.m. on the plain south of Leipzig, with artillery exchanges.

Wachau Front, morning

Around Wachau, the Allies took the offensive first and implemented their plan. They attacked in five columns.

- The first, under the command of Prussian general Friedrich Kleist von Nollendorf , set its sights on the village of Markkleeberg.

- The second, to its right, led by Duke Eugen of Württemberg (nephew of the reigning Prince of Württemberg, Napoleon's ally), advanced on Wachau.

- The 3rd, under Prince Andrei Ivanovich Gorchakov (Андрей Иванович Горчавов) , marched on Liebertwolkwitz from University Wood. These three columns featured 200 guns, with which they prepared their artillery before moving off.

- The 4th, under General Klenau, also moved towards the village, but outflanked Macdonald's Corps on the French left flank.

- The 5th column was a cavalry corps, dedicated to maintaining contact between the 2nd and 3rd columns.

On the French right, the efforts of Merveldt and Prince Frederick Joseph Ludwig Carl August of Hessen-Homburg (the future Frederick VI) were aimed at stretching the French front so that its center would open out towards Wachau. Merveldt first attempted to take the bridge over the Pleisse near Connewitz, but its destruction forced him to find a ford. The Austrians finally failed to cross the river, which was fiercely defended by General Étienne Nicolas Lefol. Further south, French riflemen distinguished themselves by holding firm at the Dölitz mill.

At Markkleeberg, Poniatowski was initially unable to resist Kleist's 19,000 fighters with his 8,000 men. But in a second phase, he came down from the nearby heights at the head of the 26th Infantry Division and recaptured the village. He abandoned it again in the face of the overly powerful 12th Prussian Brigade. The help of Augereau and effective artillery allowed him to launch a new frontal assault a little later, coordinated with a raid on Markkleeberg from the east, led by the Sémellé Division. Kleist retreated to Grosterwitz.

In the center, the coalition forces concentrated their efforts on Wachau, which was attacked by Eugen of Württemberg Corps. Victor vigorously defended the village. At around 10 a.m., Napoleon sent him two divisions of the Young Guard, led by Oudinot. Schwarzenberg gave command of the Austrian reserve to the Prince of Hessen-Homburg, and positioned him in front of the village of Cröbern, on the right bank of the Pleisse. The Austrians then tried to outflank Victor on his left, between Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz. But they came up against the Lauriston Corps, which defended furiously, especially as it in turn received support from two divisions of the Young Guard, brought in by Marshal Adolphe Édouard Casimir Joseph Mortier. Nicolas Joseph Maison, head of the 16th infantry division of the Ve Corps, advanced to the village of Güldengossa, where the enemy had dug in. Hand-to-hand combat ensued with Raïewski's Russian grenadiers for possession of the village. A detachment of the Russian Guard soon reinforced Nikolay Nikolayevich Raevsky (Николай Николаевич Раевский). Maison attempted several assaults, paying with his life to the point where he was almost taken.

During this fighting, Klenau's 4th column advanced along the road west of Seyffertshayn. He still intended to outflank the French left.

But for the French, the danger came mainly from the other wing. Kleist, who had definitively seized Markkleeberg, advanced towards Dölitz. His march was halted by Poniatowski, with the help of Édouard Jean Baptiste Milhaud's cavalry.

In the center, despite the extreme violence of the fighting, the French held firm, including the young recruits for whom it was their baptism of fire. In two hours, Wachau changed hands five times. Victor finally overcame his opponents. They seemed on the verge of breaking.

Unfortunately for the French, Macdonald was slow to carry out the turning movement to the east he had been instructed to make in order to envelop the Klenau Corps. In the meantime, at around 11 a.m., the cavalry of La Tour-Maubourg and Pajol took up positions behind the XI Corps, between Liebertwolkwitz and Holzhausen. Mortier and his two divisions of the Young Guard took up reserve positions in their rear.

Meanwhile, Napoleon had to pull back his headquarters. Enemy fire had just killed several officers there. His initial location, in the Meusdorf sheepfold on the Galgenberg hill, not far from Liebertwolkwitz and slightly behind Wachau, had been chosen too close to the front. As proof, the Guards artillery guns, installed on the reverse side of the same hill, successfully pounded the allied columns, whose ranks were gradually thinning. The Emperor withdrew his staff several kilometers to a tile factory.

At around midday, events began to move rapidly. Almost simultaneously, Napoleon learned that Gyulay's Corps had arrived in front of Lindenau, that fighting had begun at Möckern, north of Leipzig, and that the Army of the Danube was attempting a new general assault.

This one, the sixth, was pushed back like the previous ones. The French line held firm. Lauriston was firmly entrenched at Liebertwolkwitz, Poniatowski at Dölitz and Victor at Wachau. Opposing losses had already reached 12,000 men, double those of the French. Macdonald finally succeeded in his evasive maneuver and came into contact with Klenau. This one was forced to withdraw. His cavalry, defeated by Sébastiani, received help from Russian Cossacks. Klenau managed to retreat in good order and set up camp on the Kolmberg hill (also known as the "Swedish redoubt", between Liebertwolkwitz and Seyffertshayn), where he deployed a battery of 12 artillery pieces.

Lindenau Front

Despite its strategic importance − communications with Erfurt and France depend on it - the village of Lindenau was currently only held by General Margaron's weak forces. Napoleon sent Bertrand and the IV Corps to support them. In this area, the French had fourentrenchments, set up on the neighbouring heights. Four cannons were placed in a semicircle, each protecting an access road to the village. Gyulay launched three columns of attack. After several assaults, the Austrians managed to enter the village from the west. They were quickly driven out by General Bertrand's cannonballs and infantry. The battle continued until dusk in the form of an artillery duel.

Despite his 25,000 men, Gyulay was unable to wrest control of the road between Lützen and Erfurt from Bertrand. For the French, an organized retreat was still possible. In the evening, Bertrand's troops attempted a coup de main on Gyulay's camp, but a detachment of Russian light cavalry spotted them and the operation was abandoned.

Northern Front, beginning of fighting

Bluecher, at the sound of cannon fire, charged into the city to join the battle. Facing his Silesian army, Marmont and Ney were posted near the villages of Möckern and Eutritzsch, between the Elster and Parthe rivers, with Marmont occupying the most advanced position. Once in contact, Bluecher launched a furious attack on Marmont's forces. The latter was pinned down and could no longer bring help to Lindenau, Wachau or Liebertwolkwitz, as Napoleon had for a moment envisaged.

Bluecher's arrival rendered the Emperor's plans null and void. There was no longer any question facing the various enemy armies in succession. The consequences were immediate. Souham's troops, recalled by Napoleon from Düben, northeast of Leipzig, were on the march to join the Wachau front when Ney diverted them towards Möckern via Schönefeld. They could have proved invaluable in supporting Macdonald's enveloping movement. Unfortunately, Marshal Ney, who had authority over Souham, overestimated the danger posed by Marmont. III Corps played only a secondary role against Bluecher, whereas its two divisions could have had a decisive influence at Wachau.

After waiting for Souham's divisions, Ney advanced in support of Marmont. Until his arrival, Marmont was tasked with containing, at all costs, the 60,000-strong Silesian army and its hundred or so cannons. He had 20,000 to 25,000 men at his disposal.

Wachau Front, afternoon

Here, victory seemed close at hand for Grand Army. With Macdonald and Sébastiani positioned on the Allied right, Napoleon conceived a new general offensive. The artillery would continue to crush the enemy center with its cannonballs. Macdonald continued to drive the enemy reserves eastwards. Thus freed, Lauriston and Mortier marched from Liebertwolkwitz to Stormethal, while Victor and Oudinot advanced from Wachau to Güldengossa. Antoine Drouot immediately set up an 80-gun battery in the center, which struck down the Russian Imperial Guard. Mortier, on the left, was tasked with clearing the coalition positions threatening Liebertwolkwitz. Victor attacked the Auerhayen sheepfold where the Duke of Württemberg was standing. Faced with these movements, Tsar Alexander I of Russia (Александр I Павлович Романов) requested Schwarzenberg to slow down operations between the Pleisse and Elster rivers in order to prepare for the shock around Wachau.

At this point, Maison emerged from Liebertwolkwitz and pushed Gorchakov back to Güldengossa. Not far away, at the Auerhayen sheepfold, Eugen of Württemberg also retreated under the pressure of Victor and Oudinot.

However, on the left (east), Macdonald was stopped by the "Swedish redoubt". The gullied terrain prevented the French from deploying a battery sufficient to dislodge 6,000 Austrians, who were well established and also equipped with cannons. Eventually, however, the Austrians were expelled from their position.

The lack of unity in the movements of the different French Corps prevented them from drawing maximum profit of their successes.

Throughout this attack, the Guards artillery continued its shelling. The first reserve cavalry and the Guard cavalry then went into action. Joachim Murat trained ten cuirassier regiments between Liebertwolkwitz and Wachau, while Kellermann led the Spanish dragoons between Wachau and Markkleeberg. Their charges attempted to break the coalition front. They crossed its lines, as did those of Étienne Tardif de Pommeroux de Bordesoulle to the east of Güldengossa. The cavalry of the Russian Guard eventually repelled these assaults. However, a French victory seemed imminent, especially as Marmont and Ney bravely resisted to the north.

Schwarzenberg then chose to engage his reserves: the Austrian reserve cavalry under Count de Merveldt and the grenadiers of the Russian Guard under Raevsky. The latter reinforced the center, which was suffering under French artillery fire. The Allies' momentarily disturbed balance was restored. The battle became indecisive again.

On the left (west), Austrian cuirassiers cut through Victor's infantry squares and again reached Dölitz. Once again, they were repulsed.

Schwarzenberg commited fresh new troops. The Corps of Field Marshal Lieutenant Vinzenz Ferrerius Friedrich Freiherr von Bianchi relieved Kleist's Corps. The coalition troops set out again to attack French positions, capturing several of them. The fighting was fierce. Between Connewitz and the bridge over the Pleisse and beyond, the bodies of the victims, both French and Austrian, piled up several layers thick. The able-bodied troops trampled them underfoot, not caring whether they stepped on the dead or the wounded.

At around 4 p.m., sensing that the battle was tipping, the Emperor in turn called in his reserves. At Dölitz, Poniatowski received reinforcements from the Guard (Philibert Jean-Baptiste Curial division) and recaptured the village after a bayonet assault. Merveldt's Austrians retreated into the surrounding woods, but their leader and more than 1,000 of his men were taken prisoner by the Polish lancers in pursuit. The austrian general was taken to Napoleon's side, while the fighting in this sector continued well into the night.

The Austrians remained firmly attached to a manor house [51.27788, 12.38885] on the left (west) bank of the Pleisse, despite Poniatowski's bombardment attempts from the Kellerberg [51.27500, 12.40262] on the other side of the river.

The Coalitionists then intensified their thrust in the center. The French infantry, covered by Drouot's artillery, retreated under Russian cavalry charges. Maison abandoned Güldengossa for good. His division was reduced to 1,000 men. Macdonald, who had finally expelled Klenau from the The "Swedish redoubt" was now stalling in front of the University wood. His troops were not sufficiently numerous to engage there.

A particularly dark night put an end to the fighting.

Northern Front, end of operations

Bluecher sent General Fabian Gottlieb von Osten-Sacken to the Radefeld heights so that his cavalry could junction with Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg's Corps, which was arriving by the Halle causeway further north. With the support of Alexandre Louis Andrault de Langeron (Алекса́ндр Фёдорович Ланжеро́н) , Yorck captured the villages of Lindenthal and Wiederitzsch. He then moved on to Möckern, but his attacks were twice repulsed, costing him heavy losses. Langeron, meanwhile, tried to outflank the French on the right by heading towards Gohlis.

The third assault ordered by Yorck, despite deluge of artillery fire, allowed the Prussians to enter the village. The French were in the process of driving them out when Yorck brought in his cavalry and launched a general offensive around the entire perimeter of the village. The ensuing battle was one of the deadliest of the entire campaign, with 7,000 Prussians and almost as many French killed before the French could withdraw. Still, some Guards troops, formed in squares, tried to hold on to the ground. Marmont was still expecting the arrival of the Souham's III Corps, but to no avail. He finally had to give the order to retreat to the villages of Eutritzsch and Gohlis.

It was 6pm. Night has fallen. Bluecher suspended operations. Bernadotte and the Army of the North have not shown up. The Prussian general now hoped to have their support the following day.

All in all, Bluecher too failed to achieve a decisive result. He was unable to turn or take Möckern. The 12-gun battery set up in front of the village, on a site carefully chosen by Marmont near the Lindenthal woods, paralyzed his attack. The rest of VI Corps' 84 guns also proved effective, judiciously distributed on the heights. Finally, by spreading his troops out over six lines, Marmont was able to draw on a large number of reserves against an enemy forced by the terrain to follow a predetermined route.

The leader of the VI Corps could therefore pride himself on having contained forces twice his size. In the evening, he moved his units back to the left bank of the Parthe and settled in for the night at Schönefeld Castle. Souham had less reason to congratulate himself. The contradictory orders he had received had prevented his 15,000 men, with the exception of the Antoine Guillaume Delmas division, from intervening effectively . They wasted the day marching between the battlefields of Wachau and Möckern without having any influence on events.

Balance sheet

Everywhere, the fightings were extremely intense, both in Wachau and around Möckern. Many of them ended in hand-to-hand combat, with bayonets. Bluecher's losses amounted to at least 10,000 men, Marmont's to 6,000 or 7,000 soldiers (and some 50 cannons). Witnesses (including Dominique-Jean Larrey himself, surgeon-in-chief of the Grande-Armée) agree that the pyramid of severed limbs near the French ambulance was six paces high and no less in diameter.

By the evening of the first day of battle, Napoleon's plan had failed. He had not been able to defeat his enemies in detail, and Ney, in the north, had not justified his confidence. To maintain the morale of his army and his allies, he preferred to emphasize the failure of the Allies, who had not managed to win anywhere despite their numerical superiority. A message of victory was sent to Leipzig, where the King of Saxony was staying. This one was delighted with the news, but the city's population had little sympathy for it. It was not difficult to foresee that the exhaustion of Napoleon's forces, made up for the most part of young, inexperienced recruits, would be a major handicap in the face of the reinforcements pouring in from all sides towards Schwarzenberg, even if the Grande Armée had kept control of the terrain and suffered fewer losses than its opponents.

On the Allied side, Bluecher's operations around Möckern were considered a success. The patriotism of Prussian troops was galvanized.

October 17. Interlude

The troops spend the night of the 16th and 17th in the cold and mud. Straw and wood were in short supply. The next day was not much better. The weather was cold, the sky overcast and the rain incessant. The soldiers set out to forage for food in the inclement weather, but the harvest was meagre and food shortages were felt.

The break in the fighting was used to set up hospitals in the larger village buildings. However, many of these were in flames, and others had been devastated. Many of the wounded, who were arriving in ever-increasing numbers, had no place to stay and were left on the streets.

Morale in the French troops was at half-mast. Officers were forced to tighten discipline. To keep the men busy, they were employed to bury the dead of the previous day or to recover weapons scattered across the battlefield. The fate of the army preoccupied even the highest ranks. Most felt that a swift retreat was necessary. The Emperor, who had suffered a bout of fever during the night, seemed for a moment to share their opinion, before relenting.

A worrying sign was the large number of desertions and defections. Murat himself maintained contacts in the enemy camp, but this did not prevent him from continuing to fight vigorously, to the point of making the Tsar say: Really, our ally hides his game too well

.

During the morning, Napoleon surveyed the battlefield. From his point of view, the fighting would not be revived until the 19th, when Levin August von Bennigsen (Leonty Leontyevich Bennigsen, Леонтий Леонтьевич Беннигсен), Hieronymus von Colloredo-Mansfeld and Bernadotte would appear. He therefore maintained the Grande Armée on the positions of the 16th, suggesting his offensive will and reserving the possibility of claiming victory since he held the ground.

At around 2 p.m, General Merveldt was brought to Napoleon, who through him offered the allies a compromise peace. He tried to frighten Austria, insisting on the excessive weight, ambitions and half-barbaric character of its cumbersome Russian partner. Napoleon proposed resuming the negotiations begun in Prague during the Pleiswitz armistice. He declared himself ready to retreat without delay to the left bank of the Rhine, and even to include the future of Italy in the discussions.

Merveldt and his officers informed him that Bavaria, which has just changed sides, was preparing to march an army to his rear. The road to France was threatened. Retreat became essential. The difficulty of organizing a retreat for such a large army, and the Emperor's reluctance to accept the necessity, explain the continuation of the fighting.

On the coalition side, the expected reinforcements were asked to accelerate their approach. The first soon arrived: Colloredo in the morning, Bennigsen around 5pm. Bernadotte was not far behind. By midday, he had set up his headquarters in Breitenfeld, just 10 km north of Leipzig. All in all, 130,000 more men joined the coalition army. They were, however, extremely tired. So much so that Schwarzenberg, who had planned to attack during the day, decided at 2 p.m. to postpone his offensive until the following day. His simple plan was to exploit his numerical superiority to push the French back under the walls of Leipzig.

To mask these arrivals, the Allies engaged in a number of more or less successful "gesticulations". The Silesian army carried out a small operation in the north. Bluecher's cavalrymen jostled Arrighi's, but not without suffering a few losses, while Sacken came up against Dąbrowski's Polish lancers towards Gohlis. Greatly outnumbered, the latters bravely faced up to the situation, but had to retreat until they were close to Leipzig, in front of the Halle gate. As a result, the French bridgeheads on the north bank of the Parthe were reduced to a few posts protecting this entrance to the city. Bluecher thought about crossing the river for a while, but gave up when he learned that the Bohemian army was not planning to move again until the following day. All in all, the Prussian general succeeded in advancing to a line linking Eutritzsch to Gohlis.

Gyulay, for his part, received contradictory orders which led him to fight a short battle in front of Lindenau before returning to his positions of the previous day. The confusion cost him the Louis Charles Folliot de Crenneville division (a French nobleman who had gone over to the service of Austria in 1793), which had been dispatched to Cröbern at some point and could not be recalled in time.

On the French side, the only fresh troops to appear were those of the VII Corps (General Reynier): around 13,000 men, more than two-thirds of them Saxons.

While awaiting the Allies' response to his negotiating proposals, Napoleon prepared for the resumption of hostilities.

In the evening, he also made the first arrangements for the retreat. General Bertrand was put in charge. The first convoys were to head for Lützen. Non-essential equipment would be transferred to Lindenau on the night of the 17th/18th. Leipzig's defenses were reinforced, so that a rearguard would be sufficient to hold the city after the rest of the army had withdrawn. According to Napoleon's plan, the final evacuation was to take place under cover of darkness on the night of the 18th/19th.

During the particularly dark night of the 17th and 18th, despite the torrential rain and cold, Napoleon fine-tuned his strategy. This time, contrary to his custom, he fought a defensive battle. By 2 a.m., he was at the Thornberg tobacco mill, not far from Probstheida. He planned to set up his HQ there for the next day's battle. He then met Ney in Reudnitz (where the latter had moved into the former imperial HQ) and Bertrand in Lindenau. Following these visits, he decided to concentrate the Grande behind a front running from Dölitz through Dösen and Meusdorf to Holzhausen.

During these preparations, there were a few signs of disorganization. A number of ammunition caissons, for example, had to be destroyed because there were no hitches to move them. Some witnesses saw in this disorganization an echo of the Russian retreat.

October 18

The coalition now numbered 300,000. Napoleon had little more than half that number.

At around 6 a.m., the main Allied decision-makers (including the Russian Emperor Alexander I, the Austrian Emperor Francis I and the Prussian King Frederick William III, as well as Britains ambassador to Russia, Lord William Cathcart) heard Napoleon's proposals from Merveldt. They unanimously decided to leave them unanswered.

The weather changes around 8 o'clock. A steady wind dissipates the clouds and reveals the sun.

Preparatory movements

First thing in the morning on the 18th, the French divisions received orders to move closer to Leipzig. The French front thus became continuous from Poniatowski's positions in the south-west to Ney's in the northeast. What's more, the Guard, stationed behind the Thornberg, where Napoleon was standing in the center of the battlefield, was now in a position to intervene at any point. The movement was slow.

Meanwhile, the parks (artillery, ammunition, food) begin to evacuate Leipzig and begin their retreat. The narrow road from Leipzig to Lindenau soon became congested. There was only one bridge over Elster. Whether or not Napoleon, during his nocturnal visit to General Bertrand, gave the order to build more bridges remains a matter of debate.

Southern front

The Tsar, the King of Prussia and Schwarzenberg have set up their headquarters here, in Meusdorf, on the left-hand side of the road between Liebertwolkwitz and Probstheida.

Hostilities began in this sector, towards Probstheida, using artillery fire. Faced with a narrow front, the Allies' enormous numerical superiority allowed them to be content with massive assaults, neglecting the subtleties of maneuver. Their aim was to wear down the opposing forces in a battle of attrition and drive the French into Leipzig.

The coalition forces have divided their 180,000 men in this theater of operations into three columns.

- The first, on the right (east), 65,000 strong. It brought together the IV Corps of Bohemian army and Bennigsen's corps, which was in command of the whole. It advanced on Holzhausen from Grosspösna and University Wood.

- Barclay de Tolly led the second column. It comprised Gorchakov's 1st Corps, Kleist's 2nd Corps, Peter Johann Christoph Pahlen's cavalry (Pyotr Petrovich Pahlen, Пётр Петро́вич Па́лен) and a powerful artillery. The Russian and Prussian Guards formed its reserve. Its mission was to to break the French center, occupied by Marshal Victor.

- The third column, which was predominantly Austrian, was under the authority of the Prince of Hessen-Homburg. Merveldt had took back his place. Colloredo was ready to support it. It set off from Cröbern, heading for Dölitz and Markkleeberg.

Schwarzenberg's plan was to outflank the French to their left, so that the front stretched from the the Army of the North. The two coalition masses would then jointly push the enemy towards Leipzig.

On this left wing, Macdonald, flanked, was unable to hold Holzhausen with the remnants of his XI Corps. He retreated to Stötteritz, on a plateau between the Rutzschebach and Probstheida. Klenau followed and established himself opposite him. Seeing the French marshal in difficulty, the Austrian general tried to dislodge him. But Macdonald, to whom a company of Guards had just brought artillery, retaliated with a force that forced Klenau to retreat. However, even holding Stötteritz proved impossible, and Macdonald withdrew to the shelter of rugged terrain, where his troops enjoyed a few hours' respite. The situation became critical for the French in this area. While Macdonald was able to stop Klenau, he could not prevent the coalition troops from continuing their bypass operation on his left. Dmitry Sergeyevich Dokhturov (Дмитрий Сергеевич Дохтуров) advanced towards Zweinaundorf, Ferdinand von Bubna und Littitz towards Paunsdorf.

In the center, Colloredo attempted throughout the morning to seize Probstheida, which Murat and Victor defended without faltering. They were supported by La Tour-Maubourg's cavalry and a battery ofDrouot had installed in front of the village entrance. Despite the effectiveness of this artillery, the number of attackers eventually allowed Prince August of Prussia and General Georg Dubislav Ludwig von Pirch to reach the first houses. At the same time, the Russians also entered from the opposite side. They were all bayoneted back.

Napoleon, observing the battle from the Quandt mill, sent reinforcements from the Young Guard. On the other hand, he sheltered the Old Guard, which until then had been highly exposed to bombardment, by moving it south of the Thornberg. This move also had the advantage of better linking the Connewitz and Stötteritz positions.

At Probstheida, Colloredo himself led the assault, but was unable to shake the Young Guard. On the contrary, the French cavalry, led by Bordesoulle and Jean-Pierre Doumerc, overwhelmed the Russian cuirassiers, who were supported by Austrian and Prussian cavalry. Schwarzenberg called in his reserves and ordered Gyulay, on standby near Gross-Zschocher, to support the attacks on Connewitz.

On right wing, Poniatowski, Augereau and Oudinot continued to battle for possession of Dölitz, which changed hands several times between midday and 2 p.m.. At the head of the attackers, the Prince of Hessen-Homburg was wounded and had to leave his place to Bianchi. Gradually, the numerical superiority of the enemy forced Poniatowski to retreat. He took cover behind a river, then approached Augereau at Connewitz. Together, with the help of the Young Guard and its cannons, they stemmed Merveldt's advance.

However, holding Connewitz soon became difficult. The Jean-Baptiste Pierre de Semellé and Lefol divisions still held on to the village, as well as to that of Lössning, but their numbers were dwindling under enemy bombardment. However, the enemy had not yet succeeded in crossing to the east bank of the Pleisse. The Austrians had even had to abandon the Lössning woods and retreat to the Dölitz plateau.

Lindenau

While observing the fighting on the southern front, Napoleon kept a close eye on the situation in Lindenau.

In this sector, Bertrand was responsible for protecting the line of retreat with his IV Corps, reinforced by the Guilleminot division taken from the 7th. He was also authorized, if necessary, to call on the two divisions of the Young Guard, commanded by Mortier, which had been positioned in Leipzig, to reinforce the Margaron garrison.

Around 9 a.m., Bertrand received the order to start moving towards Lützen. Two hours later, he set off. Once the Austrian units posted at Klein-Zschocher had been knocked out, the road to Erfurt was no longer under enemy threat. At 2pm, Bertrand reached Weissenfels. The line of retreat was now bristling with French troops: Mortier occupied Lindenau with the Young Guard, Guilleminot held Lützen. On hearing this news, the Emperor ordered the evacuation of everything that could be evacuated to Lützen.

Gyulay, who was supposed to oppose this movement, had been hardly threatening. In his defense, erratic orders had deprived him of one of his divisions, so that he found himself outnumbered locally, the only coalition leader to experience such a situation.

North front

To the north, Marmont occupied Schönefeld, with the Delmas division in reserve. On his right, the VII Corps held Sellerhausen, reinforced by part of the 3rd Corps. Behind them, the Dąbrowski division covered Leipzig.

Opposite, Bernadotte and Blücher lined up 120,000 men. Their attack took place on the left (south-east) of the Parthe, from Taucha to Schönefeld. Yorck and Sacken remained in reserve on the right bank, their Corps having made the greatest effort on the 16th.

At 11 a.m., Langeron forded the Parthe near Mockau, then headed for Schönefeld around midday. At 1 p.m., Bernadotte also arrived on the battlefield, putting to rest the rumors that his slow arrival had sparked off.

Ney decided to attack Paunsdorf with Pierre François Joseph Durutte's division and Reynier's Saxon division. He hoped to separate the Northern and Bohemian armies. This was the moment chosen by the Saxons and the Württemberg cavalry to pass over to the enemy. A few desertions had already been reported in the morning, but suddenly seven infantry battalions between Paunsdorf and Sellerhausen, a hussar regiment and a uhlans regiment joined Bernadotte's army. They immediately began fighting their former comrades.

Meanwhile, Sacken, back in the front line, attacked Dąbrowski's Corps, which was protecting the north of Leipzig. On Ney's orders, the Michel Silvestre Brayer division came to his rescue.

In early afternoon, the snag opened up in the north by the Saxon defection was the main danger facing the Grande Armée.

At Schönefeld, the French had to retreat to fill the gaps in their front. At Paunsdorf, around 4 p.m., the Saxon artillerymen followed the example set by their fellow countrymen, both infantry and cavalry. The Durutte division in turn had to retreat to Sellerhausen. Marmont found himself in a terrible situation, and it looked as he too would have to retreat. But Schönefeld was the key to the French position on this front. The coalition forces had to seize it if they were to win. The Grande Armée's cadres, right up to the highest level, worked hard to hold the line with the remaining troops and prevent the enemy's cavalry from penetrating deep into the French position.

Ney dispatched the Delmas division to support Durutte. Napoleon himself came to Reynier's aid, with units of the Guard, the cavalry of Étienne-Marie-Antoine-Champion de Nansouty and 20 artillery pieces. His presence halted the retreat of the French second line, suddenly targeted by those who had formed the first.

The Allies step up their assault on Schönefeld.

- To their left, Matvei Ivanovich Platov (Матвей Иванович Платов) and his Cossacks came to the support of Bennigsen and Bubna.

- In the center, General Pyotr Mikhailovich Kaptzevich (Пётр Миха́йлович Капце́вич) and the Langeron Corps continued their offensive.

- On the right, Guillaume Emmanuel Guignard de Saint-Priest (another French nobleman who served the Russians) also signed up.

A bayonet fight broke out in the village streets. Langeron entered for a moment and thought he had been taken, but was driven out by a counter-attack from Ney and had to flee among his soldiers.

Schönefeld was won and lost seven times.

Finally, under pressure from the enemy artillery, while his own was silenced, Marmont ordered a slight retreat. But when the guns of III Corps and the Étienne Pierre Sylvestre Ricard division arrived as reinforcements, he took Schönefeld for the eighth time.

Marmont's heroic defense lasted until around 6pm. Langeron, who had exhausted his own ammunition, received from Bernadotte a battery of 20 well-supplied guns. The Coalitionists took the village for good. The French attempted another surprise attack at the end of the day, but it failed and they did not persist.

The violence of the engagement resulted in enormous losses. No less than eight VI Corps generals perished. Marmont himself was wounded.

Further east, the fighting was equally intense. Every hamlet was a battleground. Artillery fire was equally intense. In Pfaffendorf, a fire ravaged a hospital filled with wounded from both sides, adding another hundred victims to the day's toll. After taking Pfaffendorf, Sacken and Yorck were at the foot of the Leipzig ramparts. They attacked the Halle gate. Dąbrowski and Margaron defended it vigorously, soon assisted by a division of the Young Guard. The Allies were repulsed with heavy losses, including several generals.

Southern front

However, the fate of the battle was still being decided at Probstheida. Schwarzenberg concentrated his efforts there. In early afternoon, Peter Wittgenstein (Pyotr Khristyanovitch Wittgenstein, Пётр Христиа́нович Ви́тгенштейн) and Kleist led the reserves that set out to assault the village. Klenau supported them on their left. They are repulsed. Drouot's artillery continued to show great efficiency. After this assault, Napoleon sent Victor fresh troops drawn from the Guard: units of the Young Guard commanded by Lauriston, Louis Friant and Curial divisions of the Old Guard.

With Schwarzenberg's insistence, the village was once again the scene of hand-to-hand fighting. Hans Ernst Karl von Zieten , leading a new column, tried to enter from the west. Drouot's artillery turned him back. At around 4 p.m., the French also attacked.

The disjointed nature of the fighting, which was concentrated around a few fixation points without any overall movement, made it easier for the French to defend. What's more, some Allied units used only primitive weapons. This was the case, for example, of the Cossack Baskirs, who had only bows their disposal. The low effectiveness of their fire meant that they were unable to take advantage of their numbers and enthusiasm.

On the other hand, the Allies were testing a new system, the Congreve fuse (named after the British colonel who developed it), whose use disconcerted the first French troops targeted. This innovation was part of the evolution of combat practices, which tended towards increased use of firepower.

At the end of the day, Schwarzenberg gave up on taking Probstheida. He now intended to crush the Grande Armée with bombs and force it to retrograde. But the French line held. To the west, Poniatowski's Poles were still preventing the Allies from crossing the Pleisse. In the east, Macdonald had been holding on to Stötteritz since early afternoon.

The fighting stopped at night.

Balance sheet

Despite the good performance of their troops and their fierce resistance, the outcome of this second day of confrontation was disastrous for the French, both militarily and, above all, politically.

As on the 16th, casualties were heavy and numerous.

Thanks to their overwhelming numerical superiority (sometimes up to 3 for 1), the Allies gradually compressed the French army around Leipzig. They thus prevented it from taking advantage of its maneuvering capacity and were able to crush it under the fire of their artillery. They now glimpsed victory, the first obtained on a battlefield where Napoleon commanded. This would be a considerable success, likely to change the future of Germany. The Saxon or Württemberg corps that went over to the Allies in the middle of the battle proved this. This betrayal caused disorder that only made the unfavorable outcome of the confrontation a little more inevitable. Above all, it testified to the swing of Germanic space into the camp of the Allies, who thus achieved one of their major objectives.

On a positive note for the French: in this critical moment, and having a large number of inexperienced soldiers, the Grande Armée showed no panic and was remarkably disciplined. The young recruits were already imbued with the military values handed down by their elders. As for the latter, especially in the Guard, they refused to doubt.

In Leipzig itself, the King of Saxony, like the population, watched the confrontation from the top of towers or rooftops, and saw the stranglehold gradually tighten on the city. As the fighting drew nearer and refugees poured in from the surrounding villages, disorder set in.

During the night, French troops continued their retreat. The units concerned discovered the serious shortcomings of the measures taken in preparation for this predictable move. The disasters of the following day were the direct consequence. Another worrying symptom was the disappearance of solidarity between soldiers off the battlefield.

October 19

On the 19th, Napoleon rose at dawn to bid farewell to the King of Saxony, one of his most loyal allies.

Meanwhile, the evacuation continued. Victor, Lauriston, Reynier, Poniatowski, Augereau and Macdonald formed the rearguard, responsible for holding the city during the withdrawal. Poniatowski defended the southern part of the city with several hundred Polish soldiers. Macdonald established himself in a suburb of Leipzig, at the end of the Dresden road. Although the exits were barricaded and the walls crenellated, the position was weak, dominated by the surrounding heights. The Allies were quick to occupy them when they realized - from the sound of explosions in the artillery parks blown up by the French army, unable to take them away - that their enemy was trying to escape.

The French troops retreated along the Erfurt road, preceded by what could be saved from the artillery.

They marched in four or five columns on either side of the carriageway. Soon, the fog that had favored the first evacuations dissipated. Bluecher became aware of the movement around 9 o'clock. In this sector too, explosions signaling the destruction artillery parks soon confirmed the French withdrawal.

The Allies immediately resumed the offensive: Bennigsen and Schwarzenberg on the suburb of Würzen, Bernadotte on the districts of Leipzig facing Schönefeld. Langeron's cannons supported Schönefeld, while his skirmishers advanced towards the bridge over the Parthe River, giving access to the city.

The defenders put up a stubborn fight. They suffered from their numerical inferiority, but benefited from the Allies' determination not to cause too much damage to the city, which prevented them from making intensive use of artillery.

The Silesian army is the one that is facing the most difficulties.. The VI Corps, entrenched in a tobacco factory on the outskirts of Silesia, held out valiantly, inflicting considerable losses on the attackers. In the end, however, they were outnumbered and had to withdraw. Everywhere in the city, streets and bridges were bristling with machine-gun fire. Sheltered in houses, the remnants of the Corps de Lauriston, Reynier and Poniatowski continued their fierce resistance, shooting the invaders in what took on the configuration of an urban battle. By delaying the Allied advance, they worked to secure the Grande Armée's retreat.

Unfortunately, the retreat could only take place via the only bridge over the Elster, and was therefore very slow. Poniatowski, perhaps because Napoleon considered him the only Marshal whose morale had not been damaged, was given command of the rearguard, with the mission of holding back the enemy as long as possible. But the situation deteriorated. Desertions multiplied. Engineer Colonel Joseph Monfort (Joseph Puniet de Monfort) was given the task of undermining the bridge in order to blow it up once the last defenders of the city had crossed. However, this operation was not justified. The Elster was too narrow for the Allies to be able to build a temporary bridge across it in less than an hour. Moreover, the coalition forces located upstream or downstream, where other bridges crossed the river, would have been sufficient for pursuit, so considerable was their numerical superiority.

The responsibility for triggering the explosion was entrusted to a simple corporal, who was instructed to act as soon as the enemy appeared. A few enemy skirmishers appeared, and the corporal obeyed its orders.

With the destruction of the bridge, the situation became catastrophic and defeat became rout. The disorder already reigning in the army was followed by panic in the units trapped on the right bank of the Elster, as Marshal Macdonald would testify.

Panic spread to the troops still fighting in the town itself. After a last attempt at resistance, they capitulated. 12,000 prisoners fell into enemy hands, including Generals Reynier and Lauriston, whom the Tsar had to protect from his own soldiers, enraged by the French show of honor.

Many others, like Marshals Poniatowski and Macdonald themselves, sought to escape surrender by throwing themselves into the Elster or Pleisse rivers. Unfortunately, the steep configuration of the banks of these two rivers as well as their muddy and agitated waters, due to bad weather conditions, made the crossing difficult. Many failed and were swept away. This was the case of Marshal Poniatowski who drowned in the Elster after having crossed the Pleisse. Marshal Macdonald was luckier and managed to cross, clinging to a tree trunk, the watercourse fatal to his Polish colleague.

Those who were able to get through gathered on the road to Lindenau. The Emperor, on horseback, aides-de-camp and generals tried to rebuild the various Corps with the arrivals. But most of them no longer had any weapons or bags. They had discarded them to cross the rivers.

Despite the Allies' determination to spare it from bombardment, by the end of the battle the town had been devastated by street fighting. But that didn't stop victory celebrations. The first awards were handed out on the Marktplatz. Bluecher was appointed Field Marshal, and Klemens von Metternich was elevated to the rank of Prince. According to some Allied witnesses, the population itself expressed its joy.

Balance sheet

The Allies committed over 300,000 men, 60,000 of whom were put out of action (killed, wounded, missing). The French fielded 175,000 men and lost 60,000 to 70,000: probably 20,000 to 25,000 dead and more than 20,000 prisoners. The latter are so numerous that they would be left to starve and freeze, enduring torments reminiscent of the Russian retreat. One marshal was killed, as were several generals. Others later succumbed to their wounds.

The Battle of the Nations took the form of a collection of independent battles for possession of the villages on the surrounding plain. Under these conditions, Napoleon's tactical genius was unable to make a decisive contribution. What's more, the Grande Armée had lost in quality and maneuverability over the years. In 1813, it comprised a high proportion of inexperienced soldiers. Hence the decision - even more so than at Wagram or Borodino - to settle for a frontal assault supported by a deluge of artillery, synonymous with the slaughter of human lives. Between October 15th and 19th, French batteries fired 220,000 cannon shots, including 95,000 on the 18th.

This time, however, Napoleon was faced with insurmountable numerical inferiority. In this respect, he bore a heavy responsibility for this defeat, which his short-sightedness in retreating turned into a rout.

On the Allied side, the Battle of the Nations signaled their rallying to the warrior concepts of the French Revolution and Empire: the quest for a decisive confrontation, destroying the enemy's military capabilities in one fell swoop. This marked the advent of the "absolute war" theorized by Clausewitz, who witnessed this battle.

Consequences

Heavily defeated, the French army had to retreat to the Rhine and beyond. It would now have to defend French soil for the first time since 1794. Defeat was accompanied by total disorganization. Logistics failed, food was in short supply, and marauders, in increasing numbers, marched without respect for any orders, often preceding the columns to help themselves in the villages they passed through, looting being the soldiers' only resource.

Demoralization worsened, the marshals worried. Murat, one of the most critical, was preparing to change sides. Even the Polish officers begun to have doubts, hesitating between their loyalty to Napoleon and saving their men, now that all seemed lost.

Fortunately for the French, the Coalition army, also badly hit, was unable to mount a pursuit. Only Cossacks and irregular troops harassed the remnants of the Grande Armée.

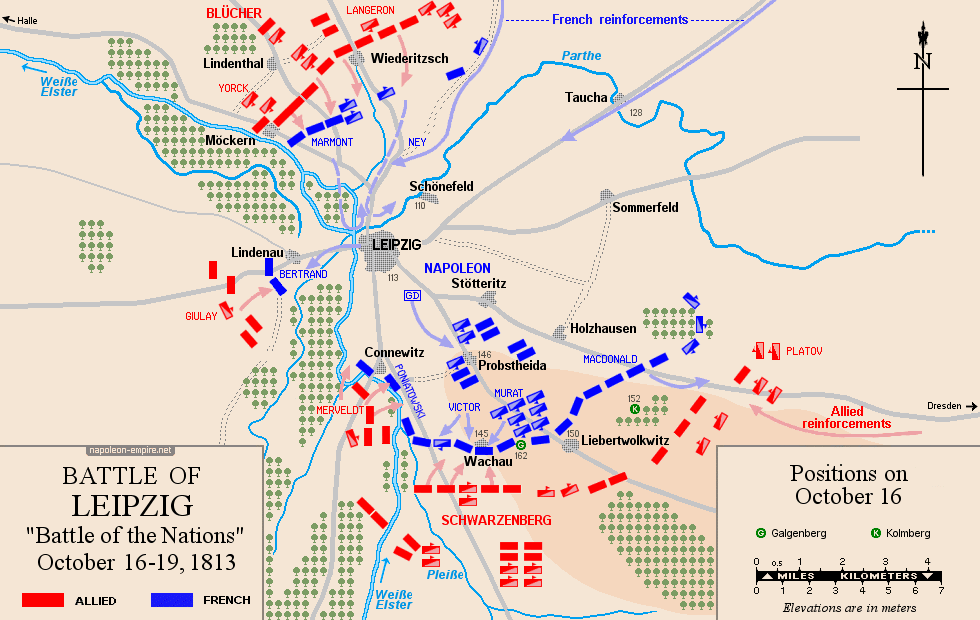

Map of the battle of Leipzig (Battle of the Nations) - Positions on October 16

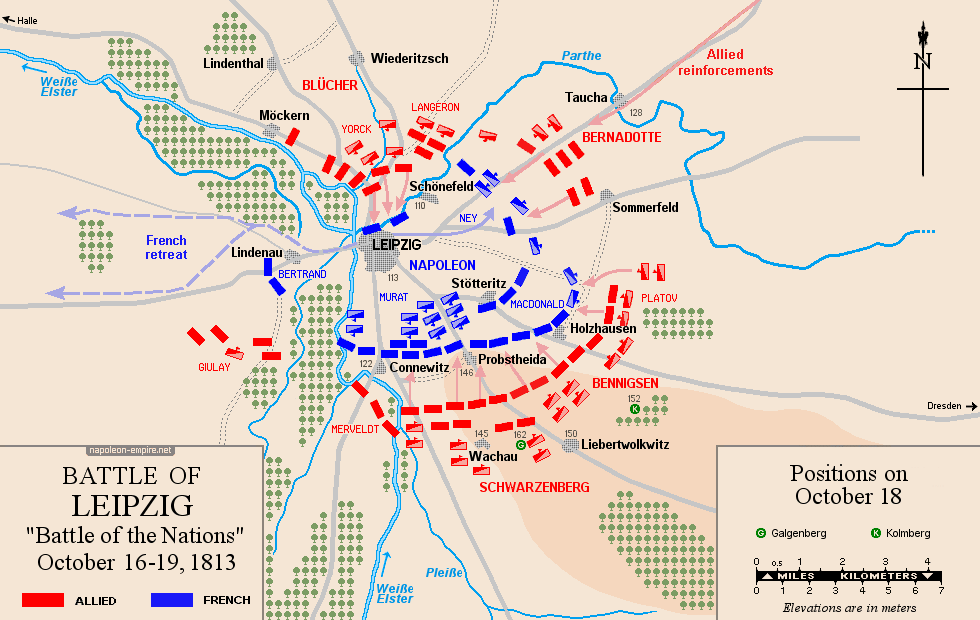

Map of the battle of Leipzig (Battle of the Nations) - Positions on October 18

Picture - "Siegesmeldung nach der Schlacht bei Leipzig". Painted 1839 by Johann Peter Krafft.

In addition to Marshal Poniatowski, the following generals were killed during the battle or died of wounds received during it:

- Claude-Charles Aubry de la Boucharderie (Major General)

- Louis Alexandre Bachelet-Damville (brigadier general)

- Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Henry Boyer (brigadier general)

- Christophe François Camus de Richemont (Brigadier General)

- Louis Jacques Coehorn (brigadier general)

- Annet-Antoine Couloumy (Brigadier General)

- Delmas (Antoine Guillaume Mauraillac d'Elmas de La Coste dit ..., Major General)

- Sixte d'Estko (brigadier general)

- Joseph (or Jacques) Martin Madeleine Ferrière (brigadier general)

- Jean Parfait Friederichs (Major General)

- Henry Maury (brigadier general)

- Aimé Sulpice Victor Pelletier de Montmarie (brigadier general)

- Honoré Vial (Major General)

- Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur de Rochambeau (division general)

The Saxons' betrayal does not appear to have been premeditated. It may simply have been the result of a refusal to die for a cause considered to be foreign, combined with the officers' desire to preserve their men at a time when casualty rates reached 30% in some regiments. It was also part of a revival of patriotic sentiment and anti-French hatred that was sweeping Germany. In the decades that followed, it gave rise to the myth of the German national "war of liberation".

Napoleon blamed the premature destruction of the Elster bridge on Colonel Montfort, who was suspended and arrested at the end of the campaign. However, they didn't dare put him before a council of war, as he himself had been left without precise instructions by the General Staff. No one had ever seriously considered the need for a retreat. When it became inevitable, no measures had been taken to organize it. It was therefore difficult to accuse the colonel without implicating the hierarchy at the highest level: the chief of engineers Joseph Rogniat, Major-General Berthier who, by virtue of his duties, should have supervised these preparations and who, if we are to believe Montfort's testimony, had refused to listen to his suggestions, and even Napoleon himself, which was unthinkable.

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.