Date and place

- October 21st, 1805 off the south-west coast of Spain, west of Cape Trafalgar.

Involved forces

- French and Spanish fleet (33 ships) under Admiral Pierre Charles Silvestre de Villeneuve.

- British fleet (27 ships) under Admiral Horatio Nelson.

Casualties and losses

- French and Spanish fleet : 3 243 killed, 2 538 injured, 8 000 prisoners.

- British fleet : 446 killed, 1 246 injured.

The Battle of Trafalgar put a definitive end to French ambitions to bring war to the English land. It came at the end of a long sequence of complex manoeuvres, intended in theory to give temporarily control of the Dover Strait (which is the narrowest part of the English Channel, separating Great Britain from France) to the imperial fleet.

Some 100,000 men, gathered on the shores of the North Sea, were ready to take the opportunity to cross the straits aboard a myriad of boats.

Overall situation

The military operations began on March 30, 1805 through the equipment of Pierre Charles Silvestre de Villeneuve’s fleet. It had left Toulon (South France, on the Mediterranean shoreline) for a long cruise that took it back to Europe on the 27th of July, to Vigo and then to A Coruña (both spanish harbors) after a loop through the West Indies where it stayed from the May 15 to June 5.

This trip was intended to deceive the English and to gather various French squadrons under a single command in order to have, at the crucial moment and on the chosen place (i.e. at the junction of the Channel and the North Sea) a sufficient numerical superiority. But it happened to be a failure. On August 15, Villeneuve, who had left A Coruña the day before in the direction of Brest(Britanny, West of France), ended up turning back to go lock himself in Cadiz (South of Spain, on the Atlantic coast), where he arrived on the 20th. As Emperor Napoleon wrote before even knowing for sure the decision taken by his admiral: Brave soldiers of the Boulogne camp! You will not go to England...

Prelude

In Cádiz

Once in Cádiz , Villeneuve focused exclusively on renewing supplies and repairing damage to his ships. The strengthening of the English fleet that was monitoring this port did not push him to take action, even though it only had 4 ships on its arrival and 11 the next day.

With at his disposal 6 excellent Spanish ships anchored in Cartagena and adding to it even only the best of his, he still had an overwhelming numerical superiority. However, he missed this opportunity and, by September 3rd, it was already almost too late. The English were then 30 to watch his anchorage.

Napoleon’s last commands

Through a letter sent on September 16th, Napoléon still commanded Villeneuve to leave his safe haven and to disembark at Naples (West coast of Italy) the troops he was carrying on his vessels and then, to return to Toulon. The admiral was also strongly advised to seek, each time he will have extra troops and ships, a decisive fight.

The French fleet was nevertheless still struggling with such difficulties as to renew its supplies. It became illusory to hope to see it weigh anchor before long, especially now that its leader was not willing to do so. Even rumours about the imminent arrival of Horatio Nelson at the head of six more ships - which would soon be proven founded - did not convince Villeneuve to set sail. Surprisingly, Napoleon, while appointing Admiral Francois-Etienne de Rosily-Mesros to take command of the squadron of Cadiz, gave him, in his letter of September 17, instructions of prudence quite opposite to the ones he had sent the day before to Villeneuve - without even informing him of his replacement. It is likely that the Emperor thought Villeneuve was too shy to obey his commands and wanted to spur him, hoping it would give him a bit of this courage he seemed to be missing so much.

Villeneuve’s postponement and apparatus

On the 7th of October 1805, Villeneuve was about to sail when he changed his mind and summoned some kind of war council, to which the general officers and the most senior captains of the fleet were invited.

He justified it to Admiral Decrés, French Minister of the Navy, through a letter sent on the 8th. In his letter, he explained that he could not remain silent in front of all the remarks coming from everywhere about the inferiority of its forces compared to the enemy’s. The English have, in front of Cadiz, from 31 to 33 vessels, of which 8 have three decks. Here, 3 Spanish vessels, fresh out of the yards, are still not ready to fight. Hence, we do not have 33 but 30 vessels. To make the choice to set sail under such conditions, with the certainty that we will have to fight, is to commit an act of despair that would be not only useless, but that would also go against the allies’ best interests!

.

All the officers that were at the meeting, to whom Napoleon's instructions were communicated under the seal of secrecy, were unanimous in considering it was necessary to wait for the favourable occasion

evoked by the Emperor to attempt an exit.

Meanwhile, Rosily was on his way to come substitute Villeneuve. He was in Madrid (the capital of Spain) on October 10 but only left on the 14th following a carriage accident. It will take him ten days more to reach Cadiz, where he will arrive after the departure of the squadron of which he was supposed to take command.

Villeneuve had been warned on the 15th of this imminent arrival - without further details. He was happy at first but when the rumours started to make him understand that the newcomer was coming to substitute him, he decided to set sail whenever he could. He immediately warned Decrès through a letter.

This occasion was offered immediately. On October 18, 1805, the weather was beautiful, the wind favorable and, in addition to that, Villeneuve had learnt that no less than 6 English vessels were unavailable to set sail for various reasons. There was no more to hesitate. On the morning of the 19th, the Franco-Spanish fleet started to leave the harbour [36.53405, -6.28860]. Villeneuve wrote to Decrès: For this departure I have only asked permission, Monseigneur, to my ardent desire to comply with the intentions of His Majesty (…)

.

Opponents’ positions

Nelson's plan: the Nelson touch

At that moment, Nelson had been in front of Cadiz since September 28th, but his presence would only be known on the 2nd of the following month because of the care he took not to be welcomed by formal greetings. Six ships and one frigate had arrived with him. Since that, he had been looking forward to a confrontation.

The English admiral already had a pretty good idea of the tactics he would use. He explained it verbally to the captains of his fleet and even left a written version of it. The reactions to his plan were unanimously enthusiastic. While he would have to face an opponent that he knew would use the most traditional tactical combinations, the English admiral chose to come up with a new tactic, based on his experience. The Nelson touch as he called it, was designed to achieve an overwhelming success. Nelson, whose open-mindness was highly contrasting with Villeneuve’s narrowness, did not doubt he was at a turning point of the fight between France and England and that he was holding between his hands the fate of the war.

On the instructions he wrote down, he planned to confront the enemy not by placing his ships side by side with the opponent’s, but by cutting his own line through an attack in columns before crushing each fraction separately. If his commands were meant to set a framework, they were careful enough not to make these commands too rigid. The admiral, showing great trust in his subordinates, gave them wide freedom in the execution of the commands.

Villeneuve’s position

Conversely, Villeneuve had no illusion on the technical value of his crews and captains. Although aware of the inadequacy of old routines in a fight against Nelson - which he even foresaw the tactical intentions quite thinly, which proves that even though he did not have the qualities of a leader, the French admiral knew his job - he nevertheless had to apply them.

The lack of initiative had for too long been part of the habits of French captains to suddenly be able to ask them to demonstrate autonomy. By his own admission, Villeneuve could only count on their courage and their love of glory.

Anticipating the rupture of its line, he gathered however the Spanish vessels in a squadron of observation and entrusted the Admiral Don Federico Gravina to go help the most endangered fractions.

The meeting of the fleets

Immediately warned of the apparatus of the allies, Nelson set sail to go block the Straits of Gibraltar (that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea, separating Europe from Africa). On the 19th, Villeneuve had managed to get out only the 9 ships of Rear-Admiral Charles René Magon. The rest of the fleet left the harbour the next day, while the weather had gone worse and the sea had grown threatening. The cape had first been set west-northwest then southwest early in the afternoon. They accompanied this change of route by a training session in three columns. At 6 a.m., the evolution was not yet complete when an English fleet got reported west-southwest. It was Nelson coming from Gibraltar.

Villeneuve immediately ordered the fleet to wear together (turnabout) and then, two hours later, to form the battle line. They decided the manoeuvre would be carried out at night, and the ships would be guided by the mizzen lantern of the ship of Admiral Gravina, placed at the front of the line. The English fleet, for its part, kept in touch through gathering.

On the 21st, at dawn, The French fleet was about 12 nautical miles from the Cape Trafalgar [36.18094, -6.03415] and was sailing towards the south in a somewhat erratic formation. The English were 10 nautical miles south-southwest of the French and were heading north-northeast. At 6:30, Nelson gave the order to sail in two columns and to sail towards the east-north-east. At that time, the weather was overcast, the sea was rough and the wind was blowing from the west-northwest.

Villeneuve, noticing the disorganization of his fleet, again ordered the formation of the line and fixed a distance of one cable length (180 meters) as the interval between the vessels. Soon, the frigates that he had sent on reconnaissance informed him about the amount of forces he would have to face. They told him 26 ships (there were actually 27) were sailing in groups and without any specific order towards his rear-guard.

With this information, Villeneuve came to the conclusion that Nelson was intending not only to overwhelm the tail of his device under the number, but also prohibit any access to Cadiz. At 8 a.m., Villeneuve commanded the fleet to wear together (turnabout) and return to Cádiz. As the battle could not be avoided, he thought it might be better to fight next to the friendliest port.

The very light wind rendered manoeuvring almost impossible and the two fleets were sailing towards the same direction until 12 p.m.

State of the operation forces

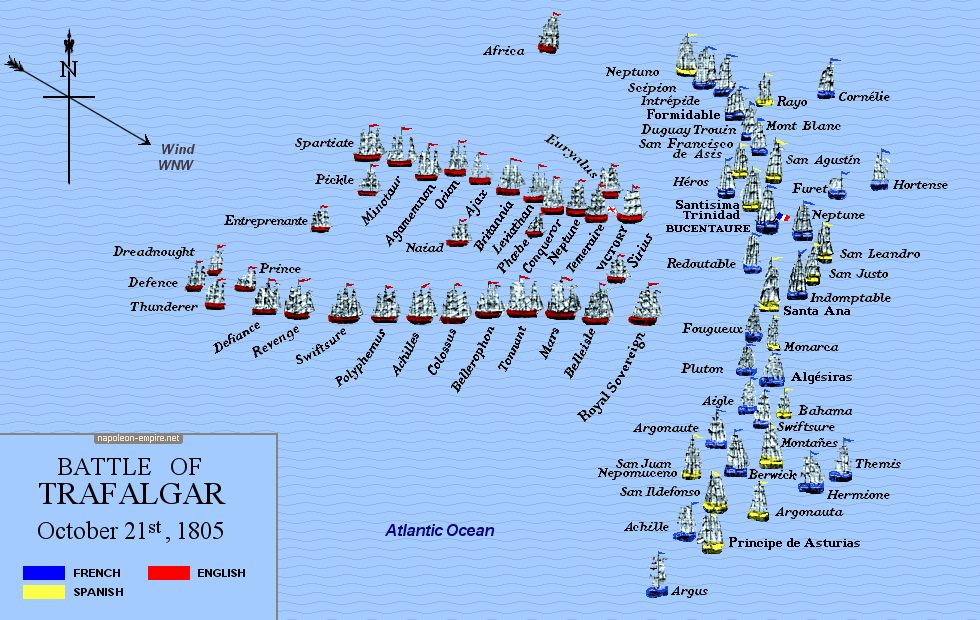

The English fleet was sailing drawn up in two parallel columns, slightly discarded.

Leading the northern, windward column Horation was Nelson himself with the following 12 ships:

- HMS Africa (two-decker, 64 guns, 498 men under the command of Captain Henry Digby ), attacking the head of the Franco-Spanish fleet

- HMS Victory (flagship, three-decker, 104 guns, 821 men under the command of Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy ) with Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson, Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet, on board)

- HMS Temeraire (three-decker, 98 guns, 718 men under the command of Captain Eliab Harvey)

- HMS Neptune (three-decker, 98 guns, 741 men under the command of Captain Thomas Francis Fremantle)

- HMS Leviathan (two-decker, 74 guns, 623 men under the command of Captain Henry William Bayntun)

- HMS Conqueror (two-decker, 74 guns, 573 men under the command of Captain Israel Pellew)

- HMS Britannia (three-decker, 100 guns, 854 men under the command of Rear-Admiral The Right Honourable Earl of Northesk )

- HMS Spartiate (two-decker, 74 guns, 620 men under the command of Captain Sir Francis Laforey)

- HMS Minotaur (two-decker, 74 guns, 625 men under the command of Captain Charles John Moore Mansfield)

- HMS Ajax (two-decker, 74 guns, 702 men under the command of Lieutenant John Pilford)

- HMS Agamemnon (two-decker, 64 guns, 498 men under the command of Captain Sir Edward Berry)

- HMS Orion (two-decker, 74 guns, 541 men under the command of Captain Edward Codrington)

and weather column as follows:

Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood led the second, leeward, column comprising 15 ships:

- HMS Royal Sovereign (three-decker, 100 guns, 826 men under the command of Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood)

- HMS Belleisle (two-decker, 74 guns, 728 men under the command of Captain William Hargood )

- HMS Mars (two-decker, 74 guns, 615 men under the command of Captain George Duff then of Lieutenant William Hennah)

- HMS Tonnant (two-decker, 80 guns, 688 men under the command of Captain Charles Tyler)

- HMS Bellerophon (two-decker, 74 guns, 522 men under the command of Captain John Cooke then of Lieutenant William Pryce Cumby)

- HMS Colossus (two-decker, 74 guns, 571 men under the command of Captain James Nicoll Morris)

- HMS Achille (two-decker, 74 guns, 619 men under the command of Captain Richard King)

- HMS Defence (two-decker, 74 guns, 599 men under the command of Captain George Hope)

- HMS Defiance (two-decker, 74 guns, 577 men under the command of Captain Philip Charles Durham)

- HMS Prince (three-decker, 98 guns, 735 men under the command of Captain Richard Grindall)

- HMS Dreadnought (three-decker, 98 guns, 725 men under the command of Captain John Conn)

- HMS Revenge (two-decker, 74 guns, 598 men under the command of Captain Robert Moorsom)

- HMS Swiftsure (two-decker, 74 guns, 570 men under the command of Captain William Gordon Rutherfurd )

- HMS Thunderer (two-decker, 74 guns, 611 men under the command of Lieutenant John Stockham )

- HMS Polyphemus (two-decker, 64 guns, 484 men under the command of Captain Robert Redmill).

An attached fleet was also composed of the following vessels:

- HMS Euryalus (frigate, 36 guns, 262 men under the command of Captain The Honourable Henry Blackwood )

- HMS Naiad (frigate, 36 guns, 333 men under the command of Captain Thomas Dundas)

- HMS Phoebe (frigate, 36 guns, 256 men under the command of Captain The Honourable Thomas Bladen Capel)

- HMS Sirius (frigate, 36 guns, 273 men under the command of Captain William Prowse)

- HMS Pickle (schooner, 8 guns, 42 men under the command of Lieutenant John Richards La Penotière)

- HMS Entreprenante (cutter, 10 guns, 41 men under the command of Lieutenant Robert Benjamin Young).

The Franco-Spanish fleet was spreading over three nautical miles, in an arc whose concavity was facing the enemy. However, far from forming a continuous and regular line, Allied ships were sailing in five groups, more or less linear, but separated from each other by excessive intervals. These 33 vessels were arranged from north to south as follows:

- Neptuno (Spain, two-decker, 80 guns, 800 men under the command of Capitán de navío Don Cayetano Valdés y Flores Bazán )

- Scipion (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Charles Berrenger)

- Intrépide (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 745 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Louis-Antoine-Cyprien Infernet)

- Formidable (France, two-decker, 80 guns, 840 men under the command of Contre-amiral Pierre-Etienne-René-Marie Dumanoir Le Pelley and of Capitaine de vaisseau Jean-Marie Letellier)

- Duguay-Trouin (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Claude Touffet)

- Mont-Blanc (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Guillaume-Jean-Noël de Lavillegris)

- Rayo (Spain, three-decker, 100 guns, 830 men under the command of Capitán de navío Don Enrique MacDonnell)

- San Francisco de Asís (Spain, two-decker, 74 guns, 657 men under the command of Capitán de navío Don Luis de Florès)

- Héros (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 690 men under the command of Capitaine de corvette Jean-Baptiste-Joseph-René Poulain then of Lieutenant de vaisseau Jean-Louis Conor)

- San Agustín (Spain, two-decker, 74 guns, 711 men under the command of Capitán de navío Don Felipe Jado Cajigal)

- Santísima Trinidad (Spain, four-decker, 136 guns, 1048 men under the command of Contraalmirante Báltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros y de la Torre and of Capitán de navío Francisco Javier de Uriarte y Borja)

- Bucentaure (France, flagship, two-decker, 80 guns, 888 men under the command of Vice-amiral Pierre-Charles-Jean-Baptiste-Silvestre de Villeneuve and of Capitaine de vaisseau Jean-Jacques Magendie)

- Redoutable (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 643 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Jean Jacques Étienne Lucas )

- San Justo (Spain, two-decker, 74 guns, 694 men under the command of Capitán de navío Don Francisco Javier Garstón)

- Neptune (France, two-decker, 80 guns, 888 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau de 1ère classe Esprit-Tranquille Maistral)

- San Leandro (Spain, two-decker, 64 guns, 606 men under the command of Capitán de navío Don José Quevedo)

- Santa Ana (Spain, three-decker, 112 guns, 1189 men under the command of Vicealmirante Ignacio María de Álava y Navarrete anf of Capitán de navío Don José Ramón de Gardoqui y Jaraveitia)

- L'Indomptable (France, two-decker, 80 guns, 887 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Jean-Joseph Hubert)

- Le Fougueux (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Louis Alexis Baudoin)

- Pluton (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau de 1ère classe Julien Marie Cosmao-Kerjulien )

- Monarca (Spain, two-decker, 74 guns, 667 men under the command of Capitán de navío Don Teodoro de Argumosa Bourke)

- Algésiras (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Contre-amiral Charles René Magon de Médine then of Capitaine de frégate Laurent Tourneur)

- Bahama (Spain, two-decker, 74 guns, 690 men under the command of Commodore Dionisio Alcalá Galiano y Pinedo )

- L'Aigle (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Pierre-Paulin Gourrège)

- Montañés (Spain, two-decker, 74 guns, 715 men under the command of Capitán de navío Francisco Alcedo y Bustamante)

- Swiftsure (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Charles-Eusèbe Lhospitalier de la Villemadrin)

- Argonaute (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Jacques Épron-Desjardins)

- Argonauta (Spain, two-decker, 80 guns, 798 men under the command of Capitán de navío Don José Antonio de Pareja y Mariscal)

- San Ildefonso (Spain, two-decker, 74 guns, 716 men under the command of Capitán de navío Don José Ramón de Vargas y Varáez)

- Achille (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Louis Gabriel Deniéport)

- Príncipe de Asturias (Spain, three-decker, 112 guns, 1113 men under the command of Almirante Don Federico Carlos Gravina then of Contraalmirante Don Antonio de Escaño y García de Cáceres and of Commodore Rafael de Hore)

- Berwick (France, two-decker, 74 guns, 755 men under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Jean-Gilles Filhol de Camas)

- San Juan Nepomuceno (Spain, two-decker, 74 guns, 693 men under the command of Commodore Don Cosme Damián Churruca y Elorza ).

An attached fleet included the following vessels, all French:

- Cornélie (frigate, 40 guns, under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau André-Jules-François de Martineng)

- Hermione (frigate, 40 guns, under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Jean-Michel Mahé)

- Hortense (frigate, 40 guns, under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Louis-Charles-Auguste Delamarre de Lamellerie)

- Rhin (frigate, 40 guns, under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Michel Chesneau)

- Thémis (frigate, 40 guns, under the command of Capitaine de vaisseau Nicolas-Joseph-Pierre Jugan)

- Furet (brig, 18 guns, 130 men under the command of Lieutenant de vaisseau Pierre-Antoine-Toussaint Dumay)

- Argus (brig, 16 guns, 110 men under the command of Lieutenant de vaisseau Yves-Francois Taillard).

So, the Allies were totalling 33 ships, to which were added 7 frigates and 2 856 guns. The English on the other hand were outnumbered and outgunned with only 27 ships and 6 frigates or corvettes, and totalling 2,314 pieces of artillery. However, they had 7 ships with three decks, when the allies only had 4 (all Spanish). In addition, their ships were generally faster, more agile, better commanded and better served by more disciplined and trained officers and crews.

Last readiness

Around 11:15 a.m., Villeneuve ordered to open fire as soon as the enemy ships would be in range, raising the cheers of his crews. Nelson, on his side, dressed with his finest uniform and most prestigious decorations before boarding the HMS Victory deck. The arrangement of his columns was not entirely according to his plans. His columns were forming a rather tormented line pointing to the French vanguard; that of Collingwood was rushing to the rear, forming a disorganized battlefront.

It was already too late to fix it. Right before the battle began, Nelson sent the famous flag signal, England expects that every man will do his duty

. Right after the sent the signal #16: engage the enemy

. At that time, the two fleets were only separated by 800 meters. It was 11:55 a.m.

The battle

First fights

Le Fougueux, the 18th vessel of the Allies' line, fired the first trial shot at Collingwood’s HMS Royal Sovereign. The ship managed to cut the enemy line, and sent the rest of her squadron on starboard side to the ships of the Franco-Spanish rear-guard. Within 20 minutes, all units between the 17th (Santa Ana) and the 33rd were struggling with Collingwood column members. The Nelson column was not yet in contact. After pretending to be heading to the vanguard, the fleet turned back and started marching against the leading allied ships.This movement, led by the HMS Victory, involved only 6 ships. The 6 others, left behind, were not taking part in the fight yet. In turn, seven of the first eight ships of the Allied line unsuccessfully cannonade the English flagship that was heading towards its opponent: The Bucentaure, its French counterpart.

A battle that was, at first, very uncertain

While fights were already going strong everywhere along the battle line, they intensified upon the arrival of the last ships. While the HMS Royal-Sovereign had already lost his grand-mast and his foremast, the HMS Victory managed to come close enough to the Bucentaure, 45 minutes after the start of the battle. The Bucentaure was escorted by Santisima Trinidad, the largest warship in the world at that time (4 bridges and more than 130 guns) and by the Redoutable, the best French ship. The three ships were navigating so tightly that it was almost impossible to slip in between them. The captain of the HMS Victory, Thomas Hardy, who had been left completely independant in his choices by Nelson, took the decision to first target the Redoutable, less powerful than the two others. To do so, he crossed the rear of the Bucentaure, firing with his 50 guns, then brutally turns on starboard, sacrificing his large parrot mast and his mizzen mast to be able to come close to the Redoutable.

It was around 1 p.m. and all the vessels were fighting except for the 8 first ships of the Franco-Spanish line. They kept sailing towards Cadiz, despite signal #5 that Villeneuve sent them and commanding that every vessel that is not on the battlefield is not at the right place and should take position that put him as close as possible to the fight

. The mêlée was fierce and it was no longer time for established tactics. The battle turned into a series of single combats, hull against hull. The riggings of the boats were destroyed. Several ships were drifting. The death toll was already very high.

Despite all their handicaps, the allies were fighting valiantly, relying on their courage and ardour. The Bucentaure was still holding on. The Redoutable did better than resisting HMS Victory. Clinging to each other, the two ships exchanged deadly shots. From now on, the survivors of their crews were firing from the planking or from the rigging that remained standing. In this situation, the French were the most precise.

Suddenly, on the quarter-deck of HMS Victory where he was galvanizing his men, Nelson collapsed. A bullet had just passed through his left lung and lodged in his spine.

He was not the only leader to get deadly wounded: Captain George Duff, of HMS Mars, died, as well as the captain of Hero, Jean-Baptiste Poulain, and the second of the Achilles; the commander of the Aigle, Pierre Gourrège, passed away at his fourth injury; Admiral Ignacio María de Álava, on the Santa Ana, got seriously wounded, as was his chief Admiral Gravina and Rear Admiral Don Antonio de Escaño, both of the Príncipe de Asturias; half of the Algeciras officers passed away ...

At 1:50 p.m., the Bucentaure again commanded the vanguard to turn towards tailwind at once

, confirming the formal order to join the battle that started at 1 p.m.

No allied vessels had yet removed his flag and surrendered. On the English side, several ships (HMS Mars, HMS Royal-Sovereign, HMS Victory) were seriously damaged. The victory could still shift from one side to the other. That is the rear-guard commanded by Pierre Etienne Dumanoir that could have the key to victory. If it keeps fleeing, the 5 or 6 English vessels that are not yet in the mêlée would make the victory shift on the English side. If it chose to intervene anything could still happen.

Attitude of Dumanoir’s squadron

The attitude adopted so far by the Rear Admiral Dumanoir is incomprehensible and unjustifiable if not by incapacity. He ended up obeying, however, and seven of his eight ships tackled, not without difficulty, some to help themselves with their canoes and two of them approaching during the maneuver, fortunately without great harm. Dumanoir then sets sail west to give his squadron time to reorganize.

Shift of fate

It is definitely southward, around the Bucentaure and the HMS Téméraire, that the fate of the battle is at stake. The flagship of Villeneuve was still in the run despite losing its grand-mast and its mizzen mast. The crew on the Redoutable was getting ready to board the HMS Victory but the size difference between the two ships is an obstacle for the French army. Only 5 men among which a midshipman, managed to climb on board of the English vessel through one of the anchor. In the meantime, the HMS Téméraire came to the rescue of its flagship by approaching the French ship on the starboard side. Thus, the French ship ended up being in between the two English vessels who were firing. Its captain however, Jean Jacques Etienne Lucas, refused to surrender. While falling due to a series of gunshot, the grand-mast of the French ship destroyed the stern of the ship. At that moment, victory clearly appeared to be on one side: the side of technical excellence.

At the back of the line, the situation was also getting worse. The last two ships, were also caught between two fires. Right in front of them, the Príncipe de Asturias was adrift, as well as the Montañés. The following seven ships were also in a bad condition and would no longer support a fight that their successive surrenders will make more and more unbalanced.

First rendering of allies

Shortly after 2 p.m., the Santa Ana, which was the first vessel in action and that had since lost its admiral, its captain and 300 men, lost its three masts simultaneously. For the few member crew still on the boats, it was the sign that it was now time to surrender. A few moments later, at 2:20 p.m., Collingwood, whose ship was so damaged that he had to switch to another vessel, HMS Euryalus, to continue his operations, surrendered, the first surrender of the battle.

The Redoutable and the Fougueux were the next two capture from the English. The first lost, killed or wounded, her captain, 12 officers out of 17, her 11 aspirants and 520 men out of 643. After the fall of her mizzen mast, she could only drift, entangled in her debris and those of the HMS Victory and the HMS Temeraire. Her condition was such that her victors were reluctant to go on board to take possession, because they feared to see her sink. That was the moment when the Fougueux, unable to govern herself either, came in her way. As a result, the HMS Temeraire released on the newcomer a lining that killed the commander, Captain Baudouin. The English crew then boarded. The Fougueux could only surrender. It was 3 p.m.

The most ardent ships of the vanguard of Dumanoir, the Neptuno and the Intrepid, finally threw themselves into the heart of the battle, to the rescue of Santísima Trinidad and the Bucentaure while the rest exchanged some guns with the enemy by focusing on the centre.

The rear-guard was defeated

South, the last vessel on the line, the San Juan Nepomuceno was the fourth to surrender. But the rest of the rear-guard was in a very bad situation as well. The Swiftsure and Algeciras had lost masts, the Achilles was on fire, the Berwick and the Argonauta were devastated. The end was near. The tactical and technical superiority of the English left no hope for Allied combatants. The Príncipe de Asturias, San Justo and San Leandro began to depart from the battle, just as, soon after, the San Francisco de Asís, the Rayo and the Hero.

The Bucentaure struck her flag

On the Bucentaure in agony, Villeneuve could not find a boat to transfer to another ship. Moreover, the closest ones were in the hands of the English and the others ones fleeing. He had the imperial eagle, the signals and the orders thrown into the sea and, at 3:30 p.m., ordered to strike the colors.

Many followed his example or did not even wait for him: the San Agustín, the Astronauta, the Swiftsure, the Aigle, the San Ildefonso, the Bahama. Dumanoir departed again, this time without any intentions of returning. Then arrived the turn of the Algeciras and Berwick to capitulate while the Achille was in flames, after losing his commander, Louis Gabriel Deniéport, his second and the Ensign that succeeded them.

End of the fights

At 4 p.m., only a dozen Allied ships remained on the battlefield, but most of them moving away from it. Only Neptune and Intrepide were still resisting. For the English, the battle was won.

Nelson, dying, had the pleasure of being informed of his victory before passing away in the arms of the commander of HMS Victory, Captain Hardy. At the same moment, or almost, the Neptuno and the Intrepid ceased the fight while the Achille, on fire, started sinking completely.

Material toll and human losses

The allies defeat was complete. Upon 33 vessels engaged in the battle, 17 have been taken by the English. One sank. Upon the 15 that managed to escape, 4 decided to flee towards the high sea under the command of Dumanoir, 11 seeked asylum in Cadiz with Admiral Gravina.

The deathtoll is of 6,500 dead or injured among which are 3,000 dead and 1,000 wounded French sailors.

Rear-Admiral Magon and 9 ship commanders were killed. 10 others were wounded, including the counter-admirals Gravina, Alaya and Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros. Villeneuve was made prisoner as well as several thousand of his men.

Here is the detailed list of what happened to each ship:

- Neptuno: saved by the allies then grounded in front of Cadiz

- Scipion: taken on the 4th of November

- Intrépide: voluntarely set on fire by the English after it was taken

- Formidable: taken on the 4th of November

- Duguay-Trouin: taken on the 4th of November

- Mont-Blanc: taken on the 4th of November

- Rayo: set on fire by the English in front of Cadix after she grounded

- San Francisco de Asís: Rescued

- Héros: Rescued

- San Agustín: voluntarely set on fire by the English after she was taken

- Santísima Trinidad: destroyed by the English after she was taken

- Bucentaure: Taken back by her crew then grounded

- Redoutable: destroyed by the English after she was taken

- San Justo: Rescued

- Neptune: Rescued

- San Leandro: Rescued

- Santa Ana: rescued by the Allies in front of Cadiz

- L’Indomptable: Rescued

- Le Fougueux: abandonned by the Engish after she was taken, then grounded

- Pluton: Rescued

- Monarca: abandonned by the Engish after she was taken, then grounded

- Algésiras: taken back by her crew

- Bahama: sunk

- L’Aigle: abandonned by the Engish after she was taken, then grounded

- Montañés: rescued

- Swiftsure: brought to Gibraltar then destroyed

- Argonaute: Rescued

- Argonauta: destroyed by the English after she was taken

- San Ildefonso: brought to Gibraltar then destroyed

- Achille: set on fire and sunk

- Príncipe de Asturias: Rescued

- Berwick: abandonned by the Engish after she was taken, then grounded

- San Juan Nepomuceno: Rescued

On the English side, 449 sailors died, including Horatio Nelson, and 1,214 were wounded. The most affected ship, the HMS Colossus, had only 40 killed while 13 ships had less than 10 dead and one of them, the HMS Prince, none. In spite of the small number of losses, the damage was such that half of the fleet, completely destroyed, had no choice but to sail to Gibraltar.

Follow up

In the following days, the English catches drasticly reduced. Some ships such as the Bucentaure and the Algeciras managed to set themselves free from the English fleet. The Neptuno and the Santa Ana were set free by Julien Marie Cosmao-Kerjulien commanding the Pluton and who had sought shelter in Cadiz after the defeat. Some ships were simply abandoned. Still others were purposely sunk or burnt because considered as too damaged to be reused or returned to a friendly anchorage. Among the four ships that made it to Gibraltar, one sunk upon arrival, two were too damaged and had to be demolished.

In total, only the San Juan Nepomuceno remained to be incorporated later in the fleet of His Majesty.

The Allies on their side only got away with the Algeciras and the Santa Ana, the Neptuno having sunk shortly after being taken back.

The French death toll got worse when the rest of Dumanoir’s squadron, i.e. the Formidable, the Scipion, the Mont-Blanc and the Dugay-Trouin came accross Commodore Richard Strachan’s way on November 2nd near Cape Finisterre. Badly led by Dumanoir, still uninspired, the battle, started on November 4, ended in a new defeat for the French and the English brought back to Plymouth 4 new catches.

In total, from all the Franco-Spanish ships that took part in the Battle of Trafalgar, only 10 survived. On the 25th of October, arriving at Cadiz, Admiral Rosily only found 5 French ships there, where he thought he had 18 to command. These 5, would never see again the French coasts since they would fall into the hands of the Spanish insurgents on June 14, 1808, shortly after the battle of Bailén.

Consequences

Trafalgar was the last great battle of the sailing navy. It definitively closed the struggle for maritime preponderance which confronted France and England for centuries and sealed the British supremacy on the seas, which would remain unchallenged until the First World War. Despite this failure, Napoleon did not give up on the development of his navy. Shipbuilding continued; ports were improved, arsenals created; the crews were reorganized on the model of the army, equipped with a uniform and a rifle and received a military training; special schools for officers were opened in Brest and Toulon. But these efforts could only be successful in the long run, and the enemy maintained control of the seas throughout the French First Empire. The racing war, revived in 1806, failed to loosen the monopoly of England on the seas. The Continental Blockade then remained the only solution to defeat England, with all the geo-strategic consequences that flew from it and that would eventually undermine the Empire and lead it to disaster.

In 1814, France no longer had a colony, no merchant fleet and the British, securing a monopoly on trade, became the world's leading power and were able to finance as long as necessary the fight of European monarchs against France and its Emperor.

Map of the battle of Trafalgar

Picture - The Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Painted 1836 by William Clarkson Stanfield.

A few moments before the battle, Nelson drafted a codicil in his will in which he demanded a reward for the services rendered by Lady Hamilton to the crown and the right to bear her name for his adopted daughter.

In accordance with his last wishes, Nelson's body was not buried at sea. He was brought back to England, kept in a barrel of brandy, and a national funeral was organized for him.

Villeneuve committed suicide on April 21, 1806, shortly after his return from captivity. It took place in Rennes, 21 rue des Foulons, in a room of the Hotel de la Patrie. He had set foot on French soil only four days earlier. The sound of his assassination circulated insistently for years, reinforced by the publication in 1825 of the memoirs of Robert Guillemard, retired sergeant. The latter gave himself up for having been almost a witness to the murder, committed according to him by a band whose leader, crossed by chance in Paris a few weeks later, wore a naval officer's uniform.

Guillemard also claimed to be the author of the fatal shot that killed Nelson. In 1830, a man named Joseph Alexandre Lardier, a former sailor, a member of the Var Academy and a future journalist in Algeria, confessed to being the author of these Apocryphal Memoirs, which were therefore only a fiction (with perhaps the collaboration of Charles Oge Barbaroux). This confession of the author will never succeed in completely destroying the legends which his work had contributed to spread. Even today, Guillemard is sometimes cited as the murderer of Nelson and the ways of Six-Fours, Toulon and Paris perpetuate his name and the memory of his feat!

On September 13, 1809, a board of inquiry composed of sailors who had never led a squadron in action, concluded that Admiral Dumanoir had manoeuvred during the Battle of Trafalgar in accordance with signals, duty and honour. The same council, on the following December 29, imputed to him a lack of decision during the days of 2, 3 and 4 November 1805. However, a council of war chaired by Admiral Ganteaume acquitted it for these same facts on March 8, 1810, stating that he had fulfilled all his duties and that his manoeuvres could not be blamed.

Two vessels named Swiftsure took part in the battle: one French (it was in fact the British ship HMS Swiftsure, which had fought in Aboukir, then was captured in 1800 in the Mediterranean and integrated into the French fleet without being renamed), the other English, launched in 1804.

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.