The institutions : the best of Napoleonic testimony

After ten years of revolution, the France of 1799 still does not have a regime capable of ensuring both the freedom of the French, their security or even its proper stability. After the constitutional kingship that shattered on the duplicity of Louis XVI, after the assembly government that degenerated into a dictatorship of committees under the pressure of war, one arrived at a strict separation of powers between a collegial executive and a bicameral parliament. In the opinion of all, or almost, it is a failure. The coups succeed each other, striking right and sometimes left, to save a Directory whose political base is becoming increasingly narrow over time.

The corruption of the regime and its military failures complete to discredit it. Its highest officials themselves are steeped in conspiracies that aim to bring it down. But Napoleon Bonaparte, the instrument they chose to carry out this task, will prove to be inconvenient and, ultimately, more skillful and more determined than them all. Not content to be the great beneficiary of the change of regime, he will impose his will and the new institutions, even if they are drafted with the help of the most eminent personalities of the time, at least those having survived the Revolution, bear his mark.

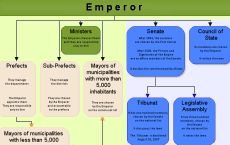

The years of the Consulate, then those of the Empire, will be years of intense institutional activity. A new political, administrative and legal framework is being set up, marked both by the consolidation of the conquests of the Revolution, mistrust of the election and the pre-eminence of the executive. Multi-camerism, reinforced by the creation of a Tribunate, serves mainly to debilitate the legislature.

The temperament of its leader and the desire to perpetuate the regime and its achievements, are rapidly changing the forms of government from a more or less seeming republicanism to theoretically hereditary monarchism. Three successive Constitutions bear witness to this evolution. The institution of a new nobility, open to all, based on merit and without privilege, completes it. This is the most ephemeral part of the construction, even if certain practices, such as the plebiscite, participate in the elaboration of the French political unconscious.

The administrative and legal framework, does survive. The prefectural organization, the Council of State, if they are not strictly speaking Napoleonic creations, then take their final form; the great Codes (civil, criminal, commercial, etc.) are written and promulgated between 1804 and 1810. All this work, considerable, will reveal an admirable solidity. Widely preserved by successors who have little suspicion of sympathy for the Revolution or the Empire, many of these institutions still function two centuries later and many of these texts still apply or serve as foundations for those who govern the French Republic.