Battle of Arcole

Date and place

- November 15th to 17th, 1796 at the Arcole bridge upon Alpone river, near its confluence with the Adige river, twenty-eight kilometers southwest of Verona, Italy (now in the province of Verona, Italy).

Involved forces

- French army (19,000 to 22,000 men, depending on the source) under the command of General Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Austrian army (21,000 to 24,000 men, depending on the source) under the command of Baron Josef Alvinczy von Borberek.

Casualties and losses

- French army: 4,000 to 6,000 men killed, wounded, missing or taken prisoner.

- Austrian army: 5,000 to 8,000 men killed, wounded, missing or captured, 11 cannons

Aerial Panorama

The Battle of Arcole, one of the most emblematic of the Napoleonic myth, was in reality a difficult, fiercely contested and long-undecided battle. For three days, the French and Austrians clashed harshly around the bridge spanning the Alpone river in front of the village of Arcole. The final victory of the French, sufficient to break the ongoing Austrian offensive, would not prevent the latter from returning to the assault two months later.

General situation

The Battle of Arcole took place towards the end of the third Austrian attempt − this time led by General Josef Alvinczy von Borberek − to liberate the town of Mantua [Mantova] . Since the beginning of June 1796, the French had been holding off, in this strategic location in northern Italy, 15,000 to 20,000 enemy troops commanded by General Dagobert Sigismund von Wurmser.

In mid-September, after his second failed rescue attempt, Wurmser was forced to lock himself inside the city. The fall of the town would open up the road to Vienna [Wien] for Napoleon Bonaparte, making its retention a vital necessity for the Austrians.

From July 1796 to January 1797, he made every effort to achieve this goal. Four large-scale attacks followed one another to achieve this goal. The fate of the third would be decided around Arcole .

As the battle was about to begin, Bonaparte had, contrary to his custom, suffered two setbacks. On the Brenta river , on November 6, and at Caldiero, on November 12, his assaults had been repulsed. The French were forced to withdraw under Verona , on the right bank of the Adige . In addition, a second enemy column, under the command of general Paul von Davidovitch, drove back the division of Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois from Trento to Rivoli Veronese .

Bonaparte devised a new plan. This involved crossing the Adige back to Ronco to attack the Austrians where they least expected it, i.e. on their left flank. At this stage of his campaign, Alvinczy could decide either to hold his ground at Caldiero, march on Verona or attempt to cross the Adige himself, which would necessarily take place between Verona and Ronco.

But, confident in the usual slowness of his opponents, Bonaparte had no fear that the situation would change considerably in the twenty-four hours it would take him to make his own move. Davidovitch had not moved since November 7 (and would remain inert until the 16th); Verona was held by a garrison of 1,500 men commanded by General Charles Édouard Jennings de Kilmaine , in whom his commander had every confidence, making the city safe from a coup de main.

Bonaparte would even welcome such an attack, which would make it easier for him to capture the town from the rear. Finally, should Alvinczy cross the Adige faster than expected, the French army would still be able to retrace its steps and attack on the right bank. At Ronco, or on the way to Ronco, the French army would be closer to Mantua than the enemy.

Beyond Ronco and as far as the Alpone (a tributary stream of the Adige, into which it flows four kilometers further south), the terrain is nothing but a vast marsh criss-crossed by dykes. Bonaparte was well aware of this, having already visited the area the previous September during operations against Wurmser. He even saw this as an advantage, provided the Austrians only held the area with weak posts, which he could easily dislodge, thus creating a base from which his troops could more easily cross than from a single bridge.

On November 14th, Bonaparte and his army set off on the march. By nightfall, they found the boat bridge established at Ronco. The Austrians, as hoped, seemed totally absent from this part of the Adige, and the bridge was built without a hitch. The French planned to cross the river at dawn the following day.

Meanwhile, Alvinczy advanced from Caldiero to San Martino [San Martino Buon Albergo] , leaving a division behind him and the Alpone . He intended to cross the Adige at Zevio on the night of the 15th to 16th with half his forces, while the rest will attack Verona.

November 15, 1796

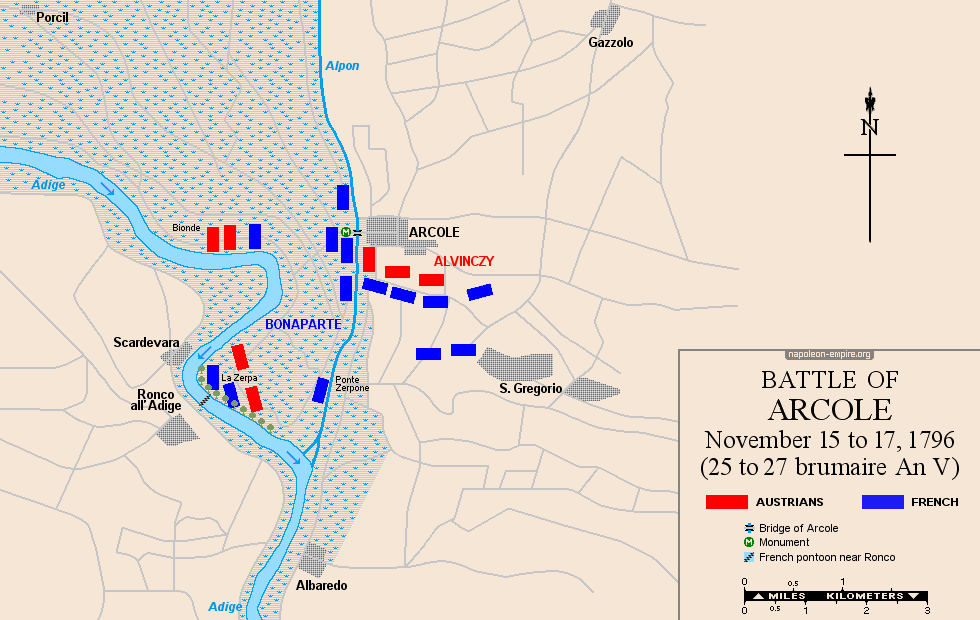

At first light, as planned, the French crossed the Adige, then split into two columns, which moved in opposite directions along the dike on the left bank. One headed for Porcil, following the course of the river upstream, the other for Arcole and the bridge [45.35731, 11.27769] that crosses the Alpone.

Bonaparte did not expect to encounter much opposition at the latter point, since the Austrians seemed content to keep an eye on the area. In any case, he could not commit all his forces to Porcil, even though this direction would bring him closer to his goal more quickly, potentially leaving his line of retreat in enemy hands.

He therefore sent Charles Augereau's division towards Arcole and André Masséna's division towards Porcil. Near the hamlet of Bionde, the latter came up against the regiment of Gabriel Anton Splény de Miháldy and a Croatian battalion. It pushed them back to Porcil and took the village, but not without encountering strong resistance.

Augereau, for his part, faced far greater difficulties. The dike used by his battalions, which ran for some two kilometers along the right bank, had its counterpart on the left bank. When the enemy arrived, the Austrians of Colonel Wenzel Karl Brigido's brigade, which held Arcole, set up their infantry there and greeted the French with musketry fire from almost point-blank range.

Augereau's vanguard turned around before reaching the bridge. He himself managed to plant a French flag on the structure, but his example was not enough to inspire his men. His generals, in turn, competed with each other to turn the tide of battle by daring and heroism. Jean Lannes, Jean Antoine Verdier , Louis André Bon and Pierre François Verne were wounded, but were unable to seize the fortress, which was defended by a few cannons and infantry entrenched in the first houses .

Seeing the situation slipping from his grasp, Bonaparte harangued his troops, reminding them of Lodi, and then, imitating Augereau, rushed to the bridge , flag in hand, without success. His aide-de-camp Jean-Baptiste Muiron was killed alongside him, and the soldiers retreated. The Austrians charge the fugitives and almost seize the general-in-chief, who was pushed into the river by the crowd. French grenadiers turned back and rescued him.

The French gave up trying to force their way through. They finally took the village at nightfall, through the brigade of General Jean Joseph Guieu. The latter, sent during the day to cross the Adige by ferry at Albaredo , south of the confluence with the Alpone, then moved up its left bank to catch the Austrians from the rear. The Austrians abandoned this position almost without a fight, as the new arrangements made by the Austrian command had rendered it unimportant.

Warned at around 10 a.m. of the passage of French soldiers on the left bank of the Adige, at Ronco, Alvinczy initially saw it only as a demonstration to scatter his units. But he gradually changed his mind and ended up redistributing his troops. He left Prince Friedrich Franz Xavier von Hohenzollern-Hechingen with his four-battalion vanguard in front of Verona, and brought himself and the rest of his forces up against the French army. Giovanni Provera, with six battalions, took up position between Caldiero and Porcil:

Anton Ferdinand Mittrowsky, with a further fourteen battalions, occupied the space between San Bonifacio to the west and San Stefano to the east. With these new arrangements, Arcole lost its position as a lock controlling access to the Austrian rear.

At the end of the fighting, Bonaparte judged his position to be mediocre. The two divisions, Augereau and Masséna, were five kilometers apart, with a marsh[now dried up] between them that was difficult to cross. It was not possible to let them spend the night in this situation. By attacking with superior forces, Alvinczy could drive them back into the marshes and cut them off from the Ronco bridge. What's more, Vaubois was still in a bad way and might have to be rescued.

On the evening of the 15th, the French gave up trying to hold on to the left bank of the Adige and moved their troops back to the other side, leaving only two half-brigades to protect the Ronco bridge.

November 16, 1796

On the morning of the 16th, Bonaparte launched his army in the same vein as the day before. But this time, Alvinczy had also decided to take the offensive. He crossed the Arcole bridge and advanced at the head of a first Austrian column, while a second, led by Provera, advanced from Porcil.

As on the previous day, Masséna drove the latter back to the hamlet, inflicting heavy losses. Augereau, for his part, pushed his opponents back beyond the Pont d'Arcole, but despite the best efforts of his troops and bravest generals, he was still unable to cross it.

Bonaparte, for his part, attempted to cross the Alpone near its confluence with the Adige, without the aid of a bridge but by means of fascines thrown into the torrent.

The attempt failed, as the current washed the bundles away. Adjutant-general Honoré Vial and his half-brigade then tried to cross on foot, even though the water was up to their shoulders, but the Austrian fire forced them to give up.

Nor was Alvinczy able to change the course of the battle. His attempt to advance his infantry from San Bonifacio to Arcole via the dykes along the Alpone failed in the face of a French company equipped with two cannons.

By evening, the situation had not changed significantly, except that Arcole was once again in Austrian hands. The French withdrew further south of the Adige, leaving a half-brigade of the Augereau division to guard the Ronco bridge.

November 17, 1796

The following day, November 17, the French resumed the offensive with somewhat modified dispositions. The results of the previous two days were generally favorable. The Austrians had lost considerably more men and material than the French, and their successes at Porcil were more than compensated for their failures at Arcole.

In these conditions, Napoleon, having now taken the measure of his adversary, was entitled to consider that an additional attack could convince Alvinczy to withdraw.

The new plan called for an assault on Arcole by the bulk of the Masséna division, of which only half a brigade would be detached and deployed in front of Porcil to lock the dike. The Augereau division was to cross the Alpone on a trestle bridge built during the night below Arcole. Finally, the Legnago garrison sent two battalions and a few cannons to divert the Austrians' left flank and rear.

At daybreak, when the French had not yet begun to cross to the left bank of the Adige, Alvinczy advanced his vanguards on the Porcil and Arcole dikes.

Perhaps the Austrian general had been misinformed by one of his spies, who told him of Bonaparte's retreat to Mantua. This was the moment that the Ronco bridge chose to break. Augereau's two half-brigades, left on guard on the left bank, were thus in great danger.

Fortunately for the French, the Austrians appeared on the two causeways along the Adige River, both upstream and downstream of the bridge, so that French artillery from the other bank was enough to stop them long enough to repair the bridge. Two half-brigades of the Masséna division immediately crossed the bridge, one heading for Porcil, led by Masséna himself, the other taking the road to Arcole, guided by General Jean Gilles André Robert . Both succeeded in repelling the enemy vanguard, and the rest of the French troops crossed the river in their turn.

While two battalions of the Augereau division secured the bridge, the other fourteen crossed the Alpone as planned. The twelve-battalion Masséna division remained behind.

The two French demi-brigades that had pushed back the enemy vanguards now found themselves up against the bulk of the Austrian contingent. They in turn retreat, overwhelmed by their numbers. Masséna moved one of his remaining brigades forward to the Porcil dike, re-establishing the situation and pushing the opposing fighters back far enough so that the Ronco bridge was now safe on that side.

On the other side, General Robert also withdrew to Ronco in the face of the Austrian thrust. But the Austrians then fell into an ambush that Bonaparte had improvised during the engagement. He had hidden three of his available battalions, those of the 32nd demi-brigade, in the meadows to the right of the Arcole dike, while the other five battalions were split between the latter and the Porcil dike.

Once the Austrians − in this case a Croatian regiment − were sufficiently advanced, the 32nd demi-brigade sprang up on their left flank, while the Porcil dike battalions assaulted their right. The Croats withdrew with enormous losses (perhaps fifty percent or more, according to Bonaparte).

Meanwhile, Augereau engaged Alvinczy's left wing. The very strong position it occupied, and the nature of the terrain, also marshy and offering only passages too dangerous to risk a column, prevented him from attempting anything decisive for a long time.

Then, perhaps, a ruse turned the tide. Bonaparte sent an officer and twenty-five guides on horseback along a path running between the marshland covering the Austrians' eastern flank and the Adige. Once on the Austrians' left, the small group's mission was to persuade them of the presence of a large cavalry contingent, using trumpet calls to good effect.

Whether he was disturbed by this stratagem, or whether the situation was enough for him, Alvinczy decided to withdraw at around two o'clock in the afternoon. Augereau had crossed the Alpone; the Austrian troops were beaten on both dykes; and they were threatened − as he had just learned − by the arrival of French reinforcements from Legnago , a town on the Adige twenty kilometers to the south.

The Austrians retreated to Villanova [now a district north of San Bonifacio], pursued by the French, who had made the junction between the Augereau and Masséna divisions after the latter had taken the road back to Arcole and crossed the village . The French left supported itself here, while the right focused on San Giorgio.

Results

The battle seems to have cost the Austrians between 5,000 and 8,000 men. French losses were probably only slightly lower, despite official assessments.

Aftermath of the battle

On November 18, Bonaparte used only his reserve cavalry to pursue Alvinczy, who continued his retreat. The bulk of the French troops came to the rescue of Vaubois, still beaten by Davidovitch on the 16th and 17th around Rivoli Veronese . The latter, who had gained the upper hand over his opposite number since the beginning of November, found himself in an extremely delicate position as a result of this major reinforcement. He realized this quickly enough to escape and withdraw on the 19th to Ala , in the Trentino region.

On the same day, Alvinczy, then at Montebello Vicentino , tried to support his lieutenant by sending a few battalions to threaten Augereau and by turning back himself on the 20th towards Villanova. Bonaparte's return to Verona , following these moves, convinced Alvinczy not to dare anything any more, and he withdrew behind the Brenta . The third attempt to unblock Mantua had failed. The sortie organized by Wurmser on the 23rd, far too late, came to nothing.

Map of the battle of Arcole

Picture - "Battle of Arcole bridge". Painted 1803 by Louis-Albert-Ghislain Bacler d'Albe.

According to the great Prussian military theorist Carl Philipp Gottlieb von Clausewitz, neither Napoleon Bonaparte nor Alvinczy showed much foresight in directing operations, with many of their decisions appearing contradictory, ill-founded and difficult to justify. In the end, in his opinion, victory went to the man who showed the most audacity and doggedness, who best led the partial engagements and who had the best troops at his disposal.

During the Arcole military operations, Napoleon Bonaparte's headquarters were :

- Villafranca di Verona on the evening of November 14;

- Ronco all'Adige [now the town hall] thereafter.

An obelisk , erected in 1810 at the mouth of the Pont d'Arcole, on the right bank of the Alpon, commemorates the French victory. It is Italy's only surviving monument to a Napoleonic victory.

André Estienne (1777-1837), a drummer in the 51st demi-brigade de ligne, became a Napoleonic legend on November 16, 1796. On that day, when Bonaparte and his men were having the most difficult of times trying to take control of the Pont d'Arcole, he threw himself into the Alpone, crossed the river holding his drum out of the water and, when he reached the opposite bank, beat the charge.

This dazzling feat earned him numerous awards. In 1802, the First Consul awarded him a pair of "baguettes d'honneur", accompanied by a patent saluting his bravery. On July 15, 1804, Napoleon himself pinned the Cross of the Legion of Honor to his chest. On December 2 of the same year, the Emperor chose him to be the lone drummer at the coronation ceremonies.

Later, his effigy was depicted on the pediment of the Pantheon and on the Etoile triumphal arch, as a symbol of courage and loyalty. Finally, in 1894, his native village of Cadenet, a small Provencal town he had left in 1792 as a volunteer to join the nation's armies, erected a statue to the "little drummer of Arcole".

Display the map of the First campaign in Italy (1796-97)

Display the map of the First campaign in Italy (1796-97)

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.