Count of the Empire

Pronunciation:

Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès was born in Fréjus, Provence, on May 3, 1748, into a modest family that is sometimes misrepresented as noble.

He was educated first by the Jesuits in his native town, then by the Congrégation de la doctrine chrétienne in Draguignan. Tempted by a military career, he nevertheless opted for the priesthood, on the advice of his parents, who were very pious and had some connections in religious circles. He entered the minor seminary of Saint-Sulpice in Paris in 1765, followed by Saint-Firmin in 1770. Siéyès was ordained a priest in 1772. Two years later, he obtained a licentiate in theology, but stopped his studies there.

Appointed to Brittany in 1775 by the bishop of Tréguier, Monseigneur de Lubersac, Siéyès resided there only intermittently, as did his superior, since it was in Paris that ecclesiastical careers were made. His own (canon in 1778, chaplain to an aunt of the King), while not brilliant, provided sufficient material security to enable him, in 1781, to cede the benefit of a second canonry to a younger brother. During these years, Siéyès represented the clergy at the Estates of Brittany, giving him his first experience of the workings of an assembly. He claimed to have returned from the assembly outraged by the way the Third Estate [Tiers-État] was treated.

In 1780, he followed his bishop, who had become a friend, to Chartres, where he was appointed grand vicar, then vicar-general and, once again, canon. At the same time, Siéyès continued his political and legal education, first as a commissioner at the Chambre souveraine du clergé de France, a position he obtained in 1786, then, the following year, as a member of the provincial assembly of Orléanais, where he met Antoine Lavoisier.

During the last six months of 1788, he wrote three pamphlets, the last of which, published anonymously at the beginning of 1789, was to become a milestone. Qu'est-ce que le Tiers-Etat ? was a huge success. Reissues followed, 30,000 copies were sold and a million people read them. The substance of the text, extremely radical, denied the privileged orders their place in the Nation, outlawed the nobility and called on the representatives of the Third Estate to form a National Assembly; the form was brilliant, punctuated with shocking and provocative formulas that hit the nail on the head and stayed in the memory.

Il y a donc un homme en France

, wrote Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti de Mirabeau to Siéyès on February 13. The now-famous canon quickly came into contact with the men who would drive the early years of the Revolution: Mirabeau, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Adrien Duport, the Lameth brothers, Nicolas de Condorcet... He also frequented the salons and joined various clubs, including the Société des Amis de la Constitution, known as the Club Breton, which later became the Club des Jacobins, of which he was one of the first members. His relationship with the Duc d'Orléans is less well known. Siéyès himself vigorously defended himself, without ever being able to completely clear himself, from the accusation of having been the instrument of this prince.

After unsuccessful attempts to have himself elected by the clergy, Siéyès was finally designated by the Paris Tiers-Etat as its twentieth and last deputy, against the letter of the elective assembly's regulations and despite the ensuing disputes. The newly-elected deputy joined the Estates-General in Versailles on May 19, and on the 27th proposed a motion inviting representatives of the Clergy to join those of the Third Estate. This battle to form a National Assembly by forcing the two privileged groups to sit with the Tiers-Etat, on pain of being excluded from representation, was a first but fundamental stage in the Revolution. Sièyès played the leading role and was permanently in the vanguard. The principles finally laid down were those described in his opuscules.

Sièyés, who had become one of the most important figures in the assembly, sat on the Constitution Committee. His influence was vigorously exerted on the drafting of the Bill of Rights, even though the drafts he presented were not accepted as they stood. The right to work, the right to relief and the right to reform the Constitution at any time were thus abandoned.

In the months that followed, Siéyès' interventions on the subjects under discussion met with varying degrees of success. He supported decrees favorable to Protestants and Jews, but opposed in vain the abolition of tithes without redemption, or the confiscation of Church property. As a result, his prestige was greatly diminished, even though he eventually voted for the civil constitution of the clergy, albeit without ever taking the oath required of ecclesiastics. He also rejected any right of veto for the King, as well as the establishment of a bicameral parliament, but was only followed on the second point. Although the new administrative organization of France into departments owed much to him, his proposed divisions were distorted by the assembly. The same applied to his ideas on a new judicial organization. Finally, his position on freedom of the press, which he intended to regulate by law, was perceived as liberticidal.

So much so that when Siéyès was finally elected President of the Assembly, after several unsuccessful attempts, it was more a recognition of his eminent role in the Revolution than a genuine endorsement of his candidacy. Moreover, the ideas of the Jacobin Club were moving further and further away from his own. Siéyès left the club to help found the Feuillants in July 1791. He was no longer part of the revolutionary avant-garde, but had moved closer to the moderates. By the time the Constituante broke up in September, he had long since taken little part in its debates.

During the Législative, Siéyès, who had retired to Auteuil, maintained close contact with the Girondin deputies.

He did not, however, join their group after his election to the Convention as deputy for Sarthe − he had also been nominated by Gironde and Orne − but sat in the Centre, also known as the Plaine or Marais. His policy seems to have been not to put himself forward. He voted for the King's death and against the appeal to the People; he refused to stand as a candidate for the Comité de Salut Public when the Comité de défense, of which he was a member, took on this new name and the new powers that went with it; he accepted the creation of the Tribunal révolutionnaire and the laws against émigrés; he kept silent or was absent during the great days of May 3 and June 2, without even joining in the subsequent protests against the resulting impeachment of twenty-two of his fellow deputies.

His major contribution during this period was a project for free education presented by the Comité d'Instruction Publique, which he chaired and which included Pierre Daunou and Joseph Lakanal. But the project was rejected by the Montagnarde majority, who viewed Siéyès with suspicion. He was soon excluded from the committee.

During the Terror, Siéyès made few appearances at the assembly and avoided opposing Maximilien Robespierre in any way, voting for the main measures demanded by the Incorruptible. He only just managed to safeguard his dignity by skilfully avoiding the abjuration to which many former ecclesiastics had to submit. However, his attitude suffered in comparison with the courage and steadfast refusal of Abbé Grégoire.

The fall of Robespierre owed nothing to Siéyès, but brought him back into the limelight. On March 5, 1795, he was elected to the Comité de Salut Public, then on April 20 to the Presidency of the Assembly. On the Committee, where he formed the diplomatic section with Merlin de Douai and Jean-François Reubell (Louis Otto and Karl Friedrich Reinhard were division chiefs), he was a determined opponent of England and a supporter of the policy of natural borders. He then took part in debates on the new constitution. The ideas he developed were fairly close to those of the Constitution of An VIII. But his project was unanimously rejected. Siéyès was resentful, and would henceforth be a determined opponent of the text preferred to his own. His opposition did not, however, prevent him from voting in favor of the law stipulating that two-thirds of the new members of parliament should come from the Convention.

No less than nineteen departments elected him as their representative. He joined the Conseil des Cinq-Cents as deputy for Sarthe, where he intervened on freedom of the press (which he still distrusted), education and finance. On November 27, 1795, the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques welcomed him to its political economy section. During this period, he frequented Madame de Staël's salon, where he made friends with Benjamin Constant. This did not prevent Siéyès from strongly criticizing the illegalities committed in the repression of the Conjuration des Egaux, whose expectations were the opposite of Constant's liberalism, leading the Abbé to be suspected of sympathizing with the Babouvistes.

On April 11, 1797, an assassination attempt on Siéyès brought him renewed popularity. Although he did not take part in the preparation of the coup d'état of 18 fructidor Year V, he supported it and encouraged the repression that followed. On November 21, he was elected President of the Conseil des Cinq-Cents by the Fructidorian majority.

During the Italian Campaign, Siéyès repeatedly disapproved of Napoleon Bonaparte's actions, both public and private, and finally of the treaties signed on his own authority by the victorious general. Nevertheless, Siéyès was as enthusiastic as anyone about the new hero when he returned to Paris. The two men met on several occasions, but nothing is known of their discussions or ulterior motives.

Re-elected in 1798, Siéyès applied for the post of ambassador to Prussia. He was appointed on May 8, 1798 and, despite reservations expressed by the Prussian government, arrived in Berlin at the end of June. Although Prussia remained neutral during the resumption of hostilities between France and Austria in March 1799, Siéyès' embassy, fraught with incidents, was not a resounding success. His underhand encouragement of subversive moves to establish republics in Prussia and various German principalities did little to improve his standing with the Prussian authorities.

Once again sent to the Assembly in April 1799 − this time by the Indre-et-Loire department − Siéyès was elected Director on May 16, and immediately returned to France. His relations with his colleagues soon turned sour. In the struggle between the Directoire and the assemblies, Siéyès was clearly on the side of the latter. In the end, he succeeded in imposing a change of Directors and government, placing his friends everywhere. Everyone was convinced that he intended to destroy the regime.

The polity was now dominated by the neo-Jacobins, who controled the assemblies. Conflict soon erupted between them and the new Director, whom they had brought to power but whom they now suspected of wanting to re-establish the monarchy in favor of the Duc d'Orléans or a German prince. Their press attacked him, even questioning the constitutionality of his election. Siéyès reacted by accepting a resignation that Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, Minister of War and extremely popular among the neo-Jacobins, had never offered... But the Director needed support. He rallied the moderates around him, made contact with Lafayette and perhaps Lazare Carnot, but did not make his intentions clear. His main concern was undoubtedly to preserve the gains of the Revolution in the face of the contradictory risks of counter-revolution and anarchy. So he went in search of a sword, the shortest he could find. He had thought of Barthélemy-Catherine Joubert, who was shortly afterwards beaten and killed in Novi.. He then had to make do with Bonaparte, who had arrived in Paris on October 16, and who imposed himself.

After the coup, Bonaparte quickly neutralized his mentor, showering him with honors. As provisional Second Consul, Siéyès was given the task of choosing the three definitive Consuls, and chose well. He was also responsible for appointing the tribunes and members of the Corps Législatif, after which he became the first President of the Conservative Senate. Finally, as a reward for his work, the grateful Republic offered him the national estate of Crosnes. It's like suffocating him under liberalities. Even his friends resented his acceptance of what appeared to be payment for having sold the Republic to Bonaparte.

These friends, in fact, soon proved to be the most vocal opponents of the new regime. Bonaparte kept a close eye on Siéyès, while at the same time sparing him. But the old revolutionary kept his mouth shut when the Tribunate was purged in January 1802, and did not vote against the Empire in 1804. It's not even certain that he was one of the two abstainers.

He spent the following years in virtual retirement. He came out of retirement to become one of the seven Grand Officers of the Legion of Honor in 1804, a Count in 1808, and Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of Reunion in 1813.

In 1814, Siéyès signed the act of forfeiture passed by the Senate on April 3, without having participated in the intrigues that had preceded it. He then kept a low profile during the first Restoration, until the news of the Emperor's return. Suspected of being one of the instigators, he was placed under police control and excluded from the Institut.

During the Hundred Days, Napoleon appointed him Peer of France, notwithstanding the fact that the newly-promoted man had always spoken out against the principle of an upper house and the heredity of offices and honors.

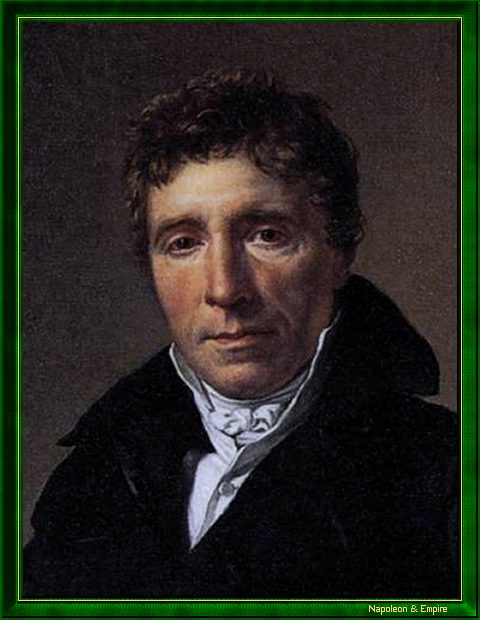

After the Second Restoration, Siéyès went into self-imposed exile in Brussels, where he founded a relief fund for destitute exiles with Jean-Jacques Régis de Cambacérès and Dominique-Vincent Ramel-Nogaret, former minister of finance under the Directoire. With the exception of Jacques-Louis David, who painted his portrait in 1817, the old revolutionary had little contact with his peers, who were numerous in the city. In 1818, the two pardons granted to regicides did not include him. He had to wait for the July Monarchy to finally return to France. In 1832, his seat at the Institut was restored.

Siéyès died on June 20, 1836. His death went largely unnoticed by the general public. His civil funeral took place two days later, and he was buried in the 30th division of the Père-Lachaise cemetery .

"Count Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès" painted in Brussels in 1817 by Jacques-Louis David (Paris 1748 - Brussels 1825).

Other portraits

Enlarge

"Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès during French Revolution". Engraving from late Nineteenth Century.

Enlarge

"Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès". Nineteenth Century engraving by William Henry Mote (St. John Horsley Down, Southwark, England ca. 1803 - St. Johns, Middlesex, England 1871).