Duke of Elchingen, Prince of the Moskowa

Pronunciation:

Michel Ney was born on January 10, 1769 in Saarlouis, Saarland, Germany. The son of a master cooper who had high ambitions for his son, Ney finished college and further education without distinction and eventually joined a regiment of hussars garrisoned in Metz (East of France) in 1787.

A non-commissioned officer at the dawn of the Revolution, he was made Lieutenant of the Rhine Army in 1792, Captain two years later and Brigadier General in August 1796 after the fall of Forscheim. Victory at Mannheim made him a général de division (Major General) in March 1799.

He became provisional Commander of the Army of the Rhine and managed to prevent the forces of Archduke Charles of Austria from crossing that river. Without these reinforcements, the troupes commanded by the Russian Souvorov were handily defeated at Zurich by André Masséna in September 1799.

The welcome he received from the First Consul, Napoleon Bonaparte, at their first meeting upon his return to Paris dispelled Ney's apprehensions about a coup d'état. He further strengthened his ties to the Bonapartes by marrying a childhood friend of Hortense de Beauharnais, Aglaé Auguié.

He served under Jean Victor Marie Moreau and took part in the victory at Hohenlinden in December 1800, which ended the War of the Second Coalition.

His career continued with an important diplomatic and military mission to Switzerland. He was charged with implementing the Act of Mediation of 1803 to avoid a civil war in the country.

After publicly endorsing the Empire in March 1804, he was selected as one of the original Marshals of France by Napoleon I on May 19 of that year.

The campaign of 1805 brought considerable success both to the Empire and to Ney: the Battle of Elchingen (October 14, 1805) led to the Austrian surrender at Ulm and played a pivotal role in subsequent successes that culminated in victory at Austerlitz on December 2.

During the Prussian and Polish campaigns of 1806-1807, Ney fought at Jena (October 14, 1806), took Erfurt (October 15, 1806) and played a key role at the Battle of Friedland (June 14, 1807).

Michel Ney was rewarded for these feats on June 8, 1808 with the title Duc d'Elchingen (Duke of Elchingen).

Two months later he left for the Iberian Peninsula. While there, he displayed a much less praiseworthy side of his personality. His irritable and jealous temperament led him to rebuke not only his commander, General Antoine de Jomini, but also his peers, Bon-Adrien Jannot de Moncey and Jean-de-Dieu Soult, and his immediate superior in the Portuguese Army, André Masséna, whose authority he accepted with difficulty. Some poorly executed, early successes gave way to much more serious failures until the Duke of Rivoli was forced to relieve Ney of his command.

His talents were once again put to good use during the invasion of Russia. Without him, victory at the Battle of Borodino would have been impossible. But it was during the retreat that he showed the full measure of his talents. In command of the rearguard, Ney courageously and doggedly withstood the Russian attacks displaying the qualities of a hero. It was largely thanks to Ney, and the several thousand men at his disposal, that the remnants of the Grande Armée escaped complete annihilation.

Napoleon I rewarded his valour by elevating him to Prince of the Moskova on March 25, 1813.

He fought again at Lützen (May 2, 1813) and Bautzen (May 21), but was defeated at Dennewitz (September 6) and wounded at Leipzig (Battle of the Nations, October 16-19).

At the conclusion of hostilities in 1814, he swiftly defected and became one of the first and most determined advocates of abdication.

Genuinely supportive of King Louis XVIII, Ney was snubbed by the court, so he departed for his estates. He only returned to the King when the Emperor landed in France, at which time he promised to bring back the usurper in an iron cage

.

However, the tactics he chose to complete his mission were ill-advised at best. On the advice of General Louis de Bourmont, the future traitor of Waterloo, a disenfranchised Michel Ney eventually embraced the Emperor's cause. A face-to-face meeting sealed their reconciliation, at least publicly: some witnesses recalled the harsh tone of the interview between the two men.

In any case, Napoleon I belatedly called upon Ney's support on June 11, 1815. The Marshal displayed little inspiration and accumulated mistake after mistake before and during the Battle of Waterloo. Once defeat became inevitable, he ostentatiously sought a soldier's death without success. In the ensuing panic, he was unable to find the Emperor. Returning to Paris, he resolved to leave the country for his own safety.

Joseph Fouché provided him with a passport and the War Minister, Louis-Nicolas Davout, signed his official leave. Nonetheless, he remained in the capital, despite knowing full well the fate that awaited him under the Restoration. Perhaps he believed himself to be protected by an article of the Convention signed by the belligerents stipulating that: All individuals in the capital will be allowed to continue to benefit from their rights and liberties and will be protected from investigation and prosecution relating to the duties they discharged currently or previously, their conduct or their political views.

A royal decree dated July 24 established a list of traitors. Marshal Ney's name was at the top.

Arrested and brought to Paris (he arrived the day of La Bédoyère's execution), he was tried before a war tribunal. The original President, Bon-Adrien Jannot de Moncey, refused to prosecute him and was replaced by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan. The other members counted among them four Marshals - André Masséna, Adolphe Edouard Mortier and Charles Augereau - and three Generals: Maison, Claparède and Vilatte.

Since Michel Ney had been named a French Peer by Louis XVIII in 1814, he demanded, according to his right, to be judged by the Chamber of Peers after the war tribunal declared itself unable to pass judgement. The Marshal, who with his lawyers and friends feared reprisals for old grudges, celebrated when his request was granted.

The trial took place between November 21 and December 6 in five sessions. Despite the convention signed by Marshal Davout with the Allies on July 3 specifying that officers and soldiers could not be prosecuted for their conduct during the Hundred Days, Marshal Ney was condemned to death "according to military regulations" by a vote of 139 to 22. Marshals Kellermann, Marmont, Pérignon, Sérurier and Victor voted in favour of execution.

The sentence was passed at midnight without the accused. Ney was awoken at three o'clock in the morning and informed of his punishment. After his wife's visit, the Marshal made a final attempt to obtain clemency from Louis XVIII and Wellington, as the Duchess d'Angoulême had done, but this failed. His execution was to take place at nine o'clock in the morning at the Carrefour de l'Observatoire in Paris, near the Luxembourg Garden.

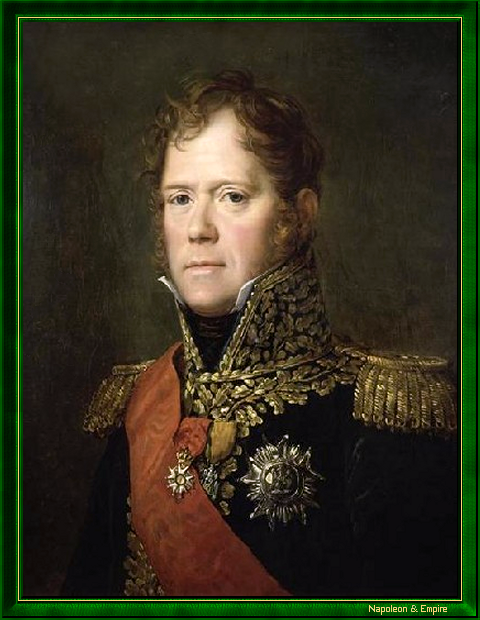

"Marshal Michel Ney" by François Pascal Simon Gérard (Rome 1770 - Paris 1837).

Calm and courageous to the end, Marshal Ney displayed the same characteristics that had served him so well in wartime. After the death sentence had been read, he went back to sleep while awaiting his wife's visit. In deference to the priest accompanying him to the place of execution, he said, After you, Father, I will be arriving ahead of everyone in the end.

In front of the firing squad he refused the blindfold offered to him saying, Have you forgotten that I have been facing the barrel of a gun for 25 years?

Freemasonry: Marshal Ney was initiated in 1801 at the "Saint Jean de Jérusalem" Lodge in Nancy, two years after Nicolas-Charles Oudinot, and was a member of the "La Candeur" ("Candour") Military Lodge attached to the 6th Corps of the Grande Armée.

The name Ney is inscribed on the 13th column (east side) of the Arc de Triomphe while a statue by Pierre Eugene Emile Hébert the Younger honouring the memory of the Prince of the Moskova can be found on the north side of the Louvre on the Rue de Rivoli . Another statue, this one in bronze, by François Rude was placed near the site of his execution on the Avenue de l'Observatoire .

He is buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris (originally in the 42nd division, but moved in 1903 to the 29th) .

Acknowledgements

Other portraits

Enlarge

"Marshal Ney". Engraving of the nineteenth century.

Enlarge

"Marshal Ney commanding the rear-guard during the retreat of Russia" by Jean-Charles Langlois (1789-1870).

Enlarge

"Marshal Ney, Duke of Elchingen, Prince of the Moskowa" by Charles Meynier (Paris 1768 - Paris 1832).